The people or the bosses

Who’s to blame for the foreclosure epidemic?

By

Sharon Black

Published Oct 26, 2008 10:03 PM

From television programs to radio talk shows—the victims of the

foreclosure crisis are being made out to be the villains. The argument goes

something like this: “People should have read the fine print” or

“People were just too impatient and wanted big houses.”

|

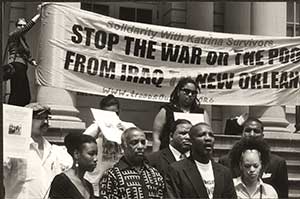

Katrina survivors and supporters, NYC.

WW photo

|

Even worse is the myth that workers in general are responsible for the crisis

“because all of us were just living beyond our means.”

Nothing could be more injurious than to blame those who are suffering for a

system that they have very little control over.

To feel ashamed and alone is a recipe that guarantees that working-class and

oppressed communities will not fight back. It also pushes individuals to take

painful desperate measures.

The case of Addie Polk, a 90-year-old widow, is one of those examples. When the

sheriff’s department came to Ms. Polk’s modest home in Akron, Ohio,

to evict her, she shot herself in the chest.

It took this kind of desperate act for Fannie Mae to allow her to stay in a

home that was originally priced at $10,000.

In Baltimore, a majority Black city, the racist, predatory lending practices of

Wells Fargo Bank are the subject of a lawsuit. The city charges that when Black

people applied to the bank for mortgages, two-thirds were told they qualified

only for the subprime mortgages. Only 15 percent of the bank’s white

customers in the same area were channeled into subprime loans.

This racist and sexist practice was multiplied across the country in Black and

Latin@ communities everywhere.

But the foreclosure problem goes far beyond just the issue of “bad

loans.” The estimated 10,000 homes foreclosed each day are tied to the

broader crisis.

With the advent of high tech and the globalization of the economy, workers have

seen their wages decline. At the same time the development of advanced

technology has pushed capitalist production higher than ever.

With wages declining—the only way that workers can either survive, or in

the case of the capitalist economy, buy back a fraction of what they

produce—is to buy on credit.

How many workers have refinanced again and again just to pay off medical bills

or for college education for their children? Who pushed credit cards and the

extension of credit? Who pushed second mortgages on homes?

Even in the case of the housing market itself, the same forces were

relentlessly at work. In every major city, rental units are overpriced. In most

major cities the cost of an apartment is now one-half or even more than the

average worker earns in a month.

The longtime standard has been that an individual should pay no more than

one-fourth of their monthly wages on housing—something that is now

virtually impossible. This situation forces workers into all sorts of deals,

including fraudulent loan schemes, just to be able to have a roof over their

head.

And the capitalists themselves are like drug addicts. Profit is a drug stronger

than heroin or anything else sold on the street. It doesn’t matter that

there are real needs like housing, food and medical care. If a profit

can’t be made, then these critical needs will not be met. And if it is

necessary to increasingly rely on credit and paper debt—no matter how

dangerous—it will be done.

The so-called dream of owning a home has now been turned into a nightmare.

If there was any benefit at all, it was that after so many years workers could

build equity in their home, which would give them some tiny sense of security,

and that maybe your children, especially if you were working class, might have

something after you died.

The present crisis has wiped that away.

Housing is a right!

In reality the dream has always been a myth under capitalism. There never has

been that much separating renters from so-called homeowners. It is the banks

that own workers’ homes and for 25 or 30 plus years workers pay

“rent” to mortgage bankers.

An immediate solution is to fight for a moratorium on all foreclosures and

evictions. A moratorium would give workers and the general community a period

of time to find larger solutions to the crisis.

The billion-dollar bailout and takeover of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac has now

elevated this demand to a federal level. The government now controls 75 percent

of the country’s mortgages. This places the responsibility of acting on

behalf of the workers at the doorstep of the federal government, which could

end all foreclosures with the stroke of a pen.

Elevating this demand politically has the potential to allow working-class

communities the confidence to proceed to more direct and immediate methods of

stopping foreclosures—that is, stopping the sheriff from removing

furniture and keeping families and individuals in their homes and

apartments.

The problem of housing must be looked at on a deeper and more profound level.

Why should housing not be readily available to all workers? Why should such a

necessity be provided solely on the basis of whether it is profitable for some

landlord, bank or real estate company?

In a country as wealthy as the U.S. there is no reason that anyone should go

homeless or find it cost prohibitive to have a roof over their head. Clean,

decent, safe and attractive housing must be a right for everyone!

Articles copyright 1995-2012 Workers World.

Verbatim copying and distribution of this entire article is permitted in any medium without royalty provided this notice is preserved.

Workers World, 55 W. 17 St., NY, NY 10011

Email:

[email protected]

Subscribe

[email protected]

Support independent news

DONATE