After casting their ballots

Mexico’s poor vote with their feet

Protest right-wing attempt to steal election

By

Teresa Gutierrez

Published Jul 5, 2006 11:31 PM

BULLETIN: As of 9 p.m. EDT on July 5, a

recount of the ballots in the Mexican presidential election shows the leftist

candidate, López Obrador, ahead of his opponent by 2 percentage points,

with almost 90 percent of the votes counted. The following article was written

earlier in the day, when the corporate media were claiming victory for Felipe

Calderón.

|

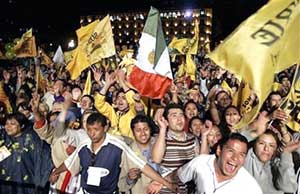

Supporters of López Obrador at the Zocalo,

Mexico City's main square, July 2.

|

As we go to press, the outcome of Mexico’s July

2 presidential election is still unknown.

For now, it is a close tie

between Felipe Calderón, candidate of the right-wing, pro-U.S. National

Action Party (PAN)—and Andres Manuel López Obrador, candidate of

the progressive Party of Democratic Revolution (PRD). Obrador is commonly

referred to as AMLO in Mexico.

Preliminary results reportedly showed an

edge for the PAN, with 36.38 percent of the vote to Calderón for

López Obrador’s 35.34 percent.

López Obrador has

called for a recount, as there are indications of voter fraud. The PRD has

compiled a list of election law violations and irregularities—including 3

million missing ballots. After he made the charge, election officials admitted

that “up to 3 million votes had not been tallied in the preliminary

results.” (New York Times, July 5)

The Washington Post reports that

a team of lawyers has been gathered, and that it may take months before the

results are known. But one thing is known. And that is that Mexico is once again

in the throes of making history.

Mexico is at a crossroads, and the

presidential election merely reflects the tumultuous contradictions that are

impacting the beleaguered Mexican masses.

The principal question is not so

much who won the 2006 elections—as important as that is—but rather:

Which way is Mexico going? How will the dire social conditions of the people of

Mexico be resolved? What role will the left now play in helping to resolve these

conditions?

Will Mexico’s sovereignty continue to be undermined by

the United States?

Can it stand with those leaders on the rise in Latin

America who are also heads of state and whose policies and political persuasion

toward the left of the political spectrum have rocked imperialism to its core?

Or will Mexico continue to be held firmly under Washington’s thumb,

resulting in an oppressive, neocolonialist and imperialist domination in the

21st century?

And most important: What is the underlying sentiment of the

Mexican masses? Which way will they go?

Will the millions of displaced

peasants, brutalized workers, homeless poor, persecuted Indigenous, unemployed

youth, and mothers with hungry children unite into one militant force that can

break the chains of oppression once and for all? Who will lead them?

Only

time will tell the answers to these questions.

But for now, the 2006

presidential election should be a reminder to the people of the United States

that everything that happens in Mexico is inextricably tied to this

country.

Not a single economic, political or social development occurs in

Mexico without Washington not only paying close attention to it but also

interfering in every way it can so that each outcome is to imperialism’s

benefit.

Over the years, U.S. economic and political institutions have

made their way deep into Mexico. The U.S. sneezes and Mexico catches the

cold.

Someone should remind CNN “journalist” Lou Dobbs of

this. His demagogic, racist rhetoric on the immigration question—an issue

intimately tied to U.S./Mexican relations—can be answered with one sole

demand: U.S. imperialism should get the hell out of Mexico so that workers will

not be forced to leave.

Mexican election, U.S.

imperialism

Fundamental change is not won through elections.

Struggle—where the masses are in motion and have heightened class

consciousness—is what brings real change. The intervention of the workers

and oppressed fighting on behalf of their own interests is decisive in making

history. They are the real agents of change, as Marxists have always pointed

out.

In the modern context, any phenomenon that takes place in the context

of a relationship between an oppressed and oppressor nation is also all about

that relationship, as Lenin explained so carefully when he updated Marx after

the rise of imperialism and finance capital.

Mexican history is rife with

U.S. intervention. Elections in Mexico take place under the heavy cloud of

imperialist domination. So in Mexico, even this basic bourgeois parliamentary

act is tainted by the smell of rotting imperialism and the threat of military

intervention.

The 2006 elections are no different.

Revolutionaries

around the world watched this election very closely. It was hoped that

López Obrador would be a contender to be another representative of the

anti-imperialist mood sweeping the Americas. In fact, his campaign theme was

“Everything for the poor.”

What a step forward for the

revolutionary camp it would be to have right at the United States’ front

door an anti-imperialist leader, a president concerned about the welfare of the

masses and not the welfare of the International Monetary Fund.

So of

course the capitalist bourgeoisie also watched this election very

closely.

From day one, the capitalist media in both Mexico and the United

States went out of their way to demonize López Obrad or. News account

after news account referred to López Obrador as a dangerous

“populist.” They compared him to Presi dent Hugo Chávez of

Venezuela, and threatened that if he were elected it would bring further

instability and even violence to Mexico.

Somehow the media forgot that in

the elections of 1988, over 500 PRD members were killed—and the

Institutional Revolu tionary Party (PRI), at that time the ruling group,

benefited from it.

One U.S. professor, a so-called expert on U.S.-Mexico

relations, called López Obrador not so much “fascistic” as

“messianic.” The U.S. ruling class was truly fearful, as

López Obrador had already shown that he was concerned about the

impoverished in his country.

As mayor of Mexico City—a significant

position held by his left-wing party—López Obrador had carried out

unprecedented social reforms.

Mayor López Obrador had launched a

comprehensive health-care program based “on social rights and

redistribution of resources,” according to the American Journal of Public

Health of December 2003. The journal further reported that a “universal

pension for senior citizens and free medical services are financed by grants,

eliminating routine government corruption and waste.”

López

Obrador promised he would push for more of the same if elected president. This

is no small thing coming from a presidential candidate in a country that shares

a 2,000-mile border with the imperial colossus of the North.

In addition,

López Obrador is reportedly against the NAFTA trade agreement with the

U.S. and Canada—which has forced so many Mexican workers and farmers to

emigrate in recent years—and would want to renegotiate its terms if

elected president. It would take political strength and will to accomplish that

goal. Can he do that without engaging the masses in a big way?

For sure,

the U.S. imperialists would find it impossible to reconcile themselves with

another Chávez at their very front door.

Mexican electoral

history

The 2006 presidential election must also be viewed in the

context of Mexico’s political history.

The U.S. media touted this

year’s election as a reflection of progress in Mexico’s fledgling

“democratic system.” They were referring to the fact that elections

in Mexico have historically been less than democratic, even within the context

of capitalist democracy.

For over 70 years, until 2000, the PRI had

attained and held the presidency through underhanded means. Selection of the

next president was commonly understood to take place not via the ballot box but

via the “dedazo” (heavy finger), with the outgoing PRI president

pointing to the next PRI president.

For over 70 years, Mexico was governed

by one-party pro-capitalist rule.

In 1988, however, that began to change.

Mexico was rocked by a mass movement that supported the progressive candidate

Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas for president.

Cárdenas was

popular for several reasons. For one, he was a leader of a faction that broke

from the PRI in a historic defection, a major upset that led to the formation of

the PRD.

Second, he was the son of Lázaro Cárdenas, a

president during the 1930s who is well respected and loved in Mexico.

Lázaro Cárdenas’s policies included defending the poor as

well as Mexico’s sovereignty, and he expropriated Mexico’s oil from

foreign domination. The Mexican masses hoped that Cuauhtémoc

Cárdenas would carry out similar policies.

On election day, news

accounts reported huge numbers of Indigenous people voting for the very first

time. Many walked hours and even days to reach a voting place.

But another

Cárdenas presidency was not to be. Despite overwhelming evidence that he

won the election, the vote was manipulated on behalf of the PRI.

The 1988

election is often referred to as the Great Election Fraud. The presidency was

handed over to Carlos Salinas. Without a doubt, Washington played a role in

throwing cold water on the mass sentiment for sweeping change.

In the next

presidential election, in 1994, the PRI maintained its increasingly shaky hold

on power. Then, in 2000, it was conveniently replaced by the more right-wing

pro-business party, the PAN.

This upset is often mischaracterized as an

example of democratization in Mexico. For example, in its reporting on the

current election, the Los Angeles Times wrote on July 4 that “popular

outrage over the [Cárdenas] vote, widely perceived as rigged, helped spur

a peaceful movement that eventually toppled the ... PRI, in 2000, after decades

of autocratic rule.”

The toppling of the PRI was no real victory for

the masses. In reality, the end of PRI dominance only meant that a more

entrenched capitalist party would carry out the bidding of both Mexican and U.S.

capitalists. A PAN victory was a mere bone thrown to the people who had poured

out for Cárdenas earlier.

Capitalist relations and the exploitation

of Mexican workers and the oppressed still stood firm.

Lessons of

1988

Without a doubt, the people of Mexico need change. Unemployment

and underemployment are at high double digits. In some neighborhoods, for some

communities, unemployment is over 50 percent.

Poverty is horrendous.

Hunger and desperation are the order of the day.

Corruption and violence

are rampant—though it’s not that the people of Latin America are

more corrupt or violent than their U.S. counterparts, but only that the

situation is publicized more. Desperation is high, however, and many are forced

to take part in the underground economy that is often violent, such as the

lucrative drug trade the United States orchestrates.

López Obrador

may be a candidate whose feet are in the camp of the poor. Should he prevail and

be the victor in this election, it could be good news for Cuba, which has

experienced strained and dangerous relations as a result of current Mexican

President Vicente Fox, formerly Coca-Cola’s top executive

there.

Last year, the Mexican establishment attempted to prevent

López Obrador from running for president by trying to send him off to

jail on ridiculous, trumped-up charges. The masses intervened. Over one and a

half million Mexicans gathered at the famous Zocalo square in López

Obrador’s defense. The right wing was forced to back off and let him

run.

But the institution controlling the election, the IFE (Federal

Electoral Institute), is reported to be allied with the PRI, which came in a

distant third, and could easily throw the election to the PAN.

Journalist

and author John Ross wrote on June 3 that the president of the IFE, Luis Carlos

Ugalde, is a figure of “ruling party interests.” In other words,

he’s tied to the PAN. Ross reported that when Antonio Villaraigosa, the

first Mexican mayor of Los Angeles since 1842, invited López Obrador to

commemorate Sept. 16 —Mexican Independence Day—in Cali fornia,

Ugalde barred López Obrador from traveling, claiming it would violate

campaign laws.

On the other hand, Ugalde gave the PAN presidential

campaign the go-ahead to canvas California for PAN votes.

What will happen

if there is another fraud and the election is thrown to the PAN? What will

López Obrador, the PRD and the left do? Will the mistakes of 1988 be

repeated?

Can the Mexican masses be rallied to take the struggle out of

the ballot box and into the streets in a mighty show of force throughout the

country? Will López Obrador or others on the left call for the people to

defend their democratic right to fair elections and take the struggle

further—raising the dire social issues and denouncing U.S. imperialism,

the root of all of Mexico’s misery?

Or will they wait six more years

for yet another election?

What role will the Zapatista Army for National

Liberation (EZLN) play in this coming period?

It should be noted that the

EZLN, during the run-up to the election, carried out what they called “the

other campaign.” EZLN leaders traveled throughout the country engaging

directly with the masses and speaking of the need for fundamental change. EZLN

spokesperson Subcom mander Marcos has made eloquent comments against capitalism

and the need for the most oppressed and the workers to take part in the

struggle.

In addition, the EZLN has clearly spoken in solidarity with

revolutionary struggles sweeping Venezuela and Bolivia and has come out against

the blockade of Cuba.

Whatever the outcome in Mexico at this juncture,

the role of the movement in the United States is to show unconditional

solidarity with the people of Mexico. It should extend solidarity to Mexican

immigrants in the United States and demand full rights for all

immigrants.

When imperialism stole one-half of Mexico and made California,

Texas and other Southwestern states part of the United States, the history of

the people of the United States was forever linked with that of the people of

Mexico.

It is time to turn that robbery around into a full-blown

anti-imperialist movement in complete solidarity with Mexico. It is time to open

the borders so that the workers of both countries can declare: “It is

profit-hungry corporations and imperialism that are illegal, not the

workers.”

Articles copyright 1995-2012 Workers World.

Verbatim copying and distribution of this entire article is permitted in any medium without royalty provided this notice is preserved.

Workers World, 55 W. 17 St., NY, NY 10011

Email:

[email protected]

Subscribe

[email protected]

Support independent news

DONATE