Student mobilization challenges racism

By

Sophie Herman

Ithaca, N.Y.

Published Nov 4, 2007 10:29 PM

Thanks in large part to a spontaneous Oct. 10 high school student walkout, the

Ithaca, N.Y., school board voted unanimously on Oct. 23 to rescind its

challenge of the state’s human rights law.

|

|

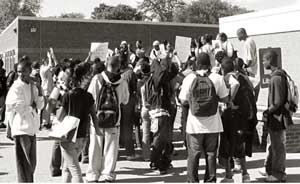

Students chant outside the administrative offices at Ithaca High School Oct. 8 to protest the way the Board of Education has dealt with recent racial incidents. Around 50 students attended the protest, which lasted about six hours.

Photo: Andy Swift/The Ithacan

|

|

It all started two years ago when an African-American student in Ithaca, the

home of Cornell University, suffered racial harassment, threats and physical

abuse in her seventh-grade year. For example, one day she was told by white

students on her school bus that there was a gun with her name on it; another

day a white student held up a sign that said, “KKK I hate

n——rs,” as she was getting off the bus.

Frustrated with the assistant principal’s inaction, the Black

student’s mother, Amelia Kearney, sent an e-mail to each member of the

board of education, but received no reply from any of the board’s nine

members. She also contacted the local police. The racist harassers were

arrested and had a restraining order placed on them. But the school, ignoring

the restraining order, placed Kearney’s daughter in the same class with

one of the harassers the following year.

Finally Kearney approached the state’s Division of Human Rights, which

determined there was probable cause of racism, and brought suit against the

Ithaca City School District on Kearney’s behalf.

But in late September, the ICSD obtained a temporary restraining order to halt

the legal process, which had been scheduled to begin Oct. 1. The district

argued that because of student privacy laws, the Division of Human Rights

should not have jurisdiction over public education.

If this challenge had succeeded, public school students across the state of New

York—in particular, students of color and LGBT students—would have

no recourse to the state Division of Human Rights.

A public outcry ensued. During a lunchtime rally in front of the Board of

Education office on Oct. 1, demonstrators stormed the office and staged a

spontaneous sit-in, demanding a dialogue with the superintendent, Judith

Pastel. She eventually agreed to talk with the demonstrators, on condition that

the dialog take place outside.

Building on the momentum, community members and high school students voiced

their outrage at a Board of Education meeting on Oct. 9. A motion was then made

by the sole African-American member of the board, Seth Peacock, for the

district to withdraw its human rights challenge and allow the Kearney hearing

to take place. The board voted 5 to 3 to postpone a vote on Peacock’s

motion, and then attempted to turn to other matters. The crowd objected

vociferously, took to the stage and shut down the meeting.

On the morning of Oct. 10, a small group of irate Ithaca High School students

refused to attend classes. They staged an impromptu march through the school

and the board office next door, swelling their ranks as they protested. The

principal, Joe Wilson, promptly locked the demonstrators out of the school

building and locked the rest of the students in their classrooms.

Wilson then sent the district’s sole African-American administrator,

Assistant Superintendent Leslie Myers, to talk to the students. She tried the

“divide and conquer” tactic by inviting the students to send a

“delegation” to sit down and talk with her, but the students would

have none of it. They insisted that if she wanted to dialog, she would have to

dialog with all of them.

Myers eventually agreed and the students aired their grievances, citing

systemic racism in the Ithaca schools, with the Kearney case being just the tip

of the iceberg. They gave numerous examples of white students and Black

students receiving different punishments for the same infraction, with a white

student often receiving a two-day suspension, or no suspension, and a Black

student receiving a two-week, four-week, or even a six-week suspension.

This double standard helps to explain why only half of Ithaca’s students

of color graduate from high school.

Principal Wilson eventually showed up at the meeting and, under pressure from

the students, agreed to hold an open forum where the student body and the

community could learn about racism in the ICSD. He promised to hold the forum

within seven school days.

Demonstrators returned to class, but made it clear over the next week that they

meant to hold Wilson to his promise. They distributed “Seven Countdown to

Equity” flyers and wore a designated color each day to represent an

aspect of their struggle.

In the ensuing week, Pastel and Wilson tried to use “racial

tensions” and “safety concerns” as a smokescreen to distract

the community from student grievances. Wilson did not keep his word about

holding an open forum. On the sixth day, Oct. 18, he held two closed meetings,

one for downtown students of color and one for rural, white students, and

denied entrance to parents and community members.

On the weekend of Oct. 20-21, the district called in the New York State Center

for School Safety and the Department of Justice to bolster the local police

presence in the high school. District administrators spent the weekend

harassing students and parents with phone calls to prevent students from

holding another rally.

But the students’ voices had been heard loud and clear by the Board of

Education. On Oct. 23, before a crowd of 200 people, the board voted

unanimously to accept Seth Peacock’s motion to rescind the human rights

challenge and allow the Kearney case to be heard.

After the revote, according to the Ithaca Journal, “Peacock thanked

Lambda Legal, a legal advocacy group that focuses on gay rights, for alerting

the board that its challenge would remove the only effective legal protection

for LGBT students. ‘I want to thank Lambda for their involvement in this

case,’ Peacock said. ‘Their letter, I think, allowed many of us to

look at this issue differently.’ ”

Building on this victory, the movement for equity in Ithaca is continuing to

call for the ouster of Pastel and Wilson and an apology from the district to

Amelia Kearney and her daughter. Students and parents want to see more ethnic

studies courses at the high school—currently there is only one; a clear

policy for dealing with racist acts in school and on school buses; and

equitable and positive disciplinary methods, as an alternative to the draconian

suspensions of students of color.

Articles copyright 1995-2012 Workers World.

Verbatim copying and distribution of this entire article is permitted in any medium without royalty provided this notice is preserved.

Workers World, 55 W. 17 St., NY, NY 10011

Email:

[email protected]

Subscribe

[email protected]

Support independent news

DONATE