April 11: 30th anniversary of Lucasville prison uprising

April 11, 2023, marks the 30th anniversary of the heroic uprising at the Southern Ohio Correctional Facility in Lucasville, Ohio. The uprising began as Muslim inmates protested against being forced to take a tuberculosis test that violated their religious beliefs against alcohol. It quickly turned into a full-scale rebellion that left a guard and several inmate hostages dead. The uprising ended with prison authorities agreeing to a list of 21 demands.

Later the authorities scapegoated a group of 50 inmates, giving most of them harsh sentences of 5 to 25 years and sending five to death row, including the prisoner leaders who had negotiated the peaceful surrender. The five — Siddique Abdullah Hasan, Keith Lamar (aka Bomani Shakur), James Were (aka Namir Mateen), Jason Robb and George Skatzes — remain on death row.

Lamar now has an execution date of Nov. 16 this year. Although Ohio currently has a moratorium on executions, the governor could lift the moratorium, putting Lamar’s life in jeopardy. Among the many events in Ohio commemorating the uprising anniversary is a fundraiser for Lamar April 14.

We republished this interview with Imam Hasan by Workers World Managing Editor Martha Grevatt, conducted on April 2-3, 2018, for the 25th anniversary of the rebellion.

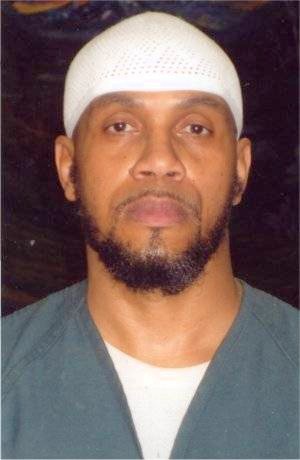

Siddique Abdullah Hasan

Martha Grevatt: What were the issues that led to the rebellion?

Imam Hasan: There was numerous issues. For example, prisoners was only given one five-minute phone call per year to speak with their family, and it was referred to as a Christmas call. The food was inadequate nutritionally and unsanitary. Visitors had to go through a lot of unnecessary and harsh treatment and disrespect from staff members.

The medical care was inadequate, and the list goes on and on. But the straw that actually broke the camel’s back would have been the planned inoculation testing. It was scheduled for April 12, that Monday — that all prisoners who had not submitted to the Mantoux tuberculin skin test, which consists of phenol.

Phenol is an alcoholic substance. It’s forbidden for Muslims to consume alcohol, to sell alcohol, to transport alcohol, to unnecessarily put alcohol on their body, to be involved in any shape, form or fashion.

We had an objection to taking that particular test, but we had no objection to submitting to one of the other forms of testing that would arrive at the same conclusion. And we asked would they be willing to take a sputum specimen. We was willing to take a chest X-ray.

If a urinalysis would have sufficed, we was willing to do that. Even as a last resort, we was willing to be quarantined. They could have quarantined us for two to three weeks, and they would have come to the determination whether we was infected by TB or not.

So at SOCF we put to Warden Tate and his subordinates various different options, but that was not good enough for them. They didn’t want prisoners to try to dictate to them how to run their institution. But we was not dictating to them, because there was a U.S. Supreme Court case, Turner v. Safley; I think it came out of the state of Missouri. And it basically says that just because a person becomes a prisoner, and these gates and doors close behind them, they do not forfeit their Constitutional rights.

Before the prison authorities try to deny a person their Constitutional rights, there are certain factors that must be considered. One of those factors would be [whether] there [are] alternative methods to arrive at the same conclusion, and we gave the institution various different options. That’s not trying to dictate to Warden Tate — Arthur Tate Jr., also known as King Arthur. We understand that [when] being confined in close quarters, disease spreads, and we understand it’s a public health issue, but by the same token we have a Constitutional right as well.

The other thing was this. The state tried to justify their action, saying it would have cost an enormous amount of allocation [of money] for some of those methods that we was asking. It would have cost the state nothing to quarantine us, because they do it all the time. They constantly moving prisoners to the Hole, moving prisoners from one side of the institution to the other, another cell to another cell.

But the problem is when you find people in authority, whether it be a Warden Tate, Donald Trump or other people, people just believe that they’re above the law and there’s no accountability, and that is the problem we ran into at Lucasville.

MG: Describe the events that began April 11, 1993.

IH: A couple of weeks before the uprising actually happened, you had about 150 people that were refusing to take the test, and people had various different reasons. Some prisoners was concerned about the Tuskegee Institute, where they used Black people as guinea pigs. As for the Muslims, we was refusing to take the test on religious grounds.

Warden Tate called myself and two other Muslims to participate in a meeting with him and some of his other top officials. We had a discussion, and our position was, once again, we want to be concerned about this public health issue, but at the same time we did not want to submit to that phenol test. Tate had no understanding. He wanted to adopt a hard-line approach; he wanted it to be his way or no way. He seen that we was trying to talk to him, have a diplomatic conversation with him or intelligent conversation with him, [but] it was falling on deaf ears.

So Muslims had decided what they was going to do. Initially it was intended to be a peaceful protest to bring it to the attention of [Tate’s] superiors in the central office at the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Corrections. And what was intended to be a peaceful protest ended up turning into a full-scale rebellion. I guess the question becomes how.

When officers start running helter-skelter and leaving prisoners unmonitored — they was more concerned about their own safety, as opposed to fulfilling their job and being concerned about prisoner safety — they left their posts. When prisoners seen that — I mean that long train of abuses that prisoners was going through: staff-on-inmate violence; staff encouraging, instigating prisoner assault among themselves; and the whole nine yards — prisoners just seen the opportunity to take advantage of a situation.

It wasn’t the Muslims’ intention, but things got out of hand. And one thing led to another. That’s how we ended up with a full-scale rebellion.

MG: Can you talk about the unity of the inmates?

IH: From the very beginning of the uprising, the majority of people who was actually murdered or who was assaulted was white. So when white prisoners seen that, they obviously became panicky, thinking it was a race riot. But after careful investigation, they came to see that these people who was actually assaulted or who was murdered was supposedly informants, snitches, whatever the case may be. And you know there’s a prison saying that “snitches get stitches.”

So some prisoners, like I said, took advantage of the opportunity to make it a full-scale rebellion and also took the opportunity to do payback on some who have actually told on other prisoners.

So when that was actually going on, the Muslims, we stepped up to the plate, and we talked to other groups such as the Aryan Brotherhood. And we wanted to bring peace and harmony to what was going on. So representatives from the Muslim community, representatives from the AB and representatives of the Black Gangster Disciples got on the bullhorn and notified prisoners that it was not inmate on inmate, contrary to how it may look.

It was us against the administration that was depriving us of many of our rights for decades upon decades. What they did; they got on the bullhorn and tried to calm peoples’ nerves.

But I think another thing was a turning point on the first day, several hours into the uprising. As Muslims we have five prayers that we must perform on a daily basis; even in a war zone, Muslims still find time to pray. So the same thing is applicable in Lucasville.

The disturbance happened at 3 [p.m.]. So we made one prayer, the midafternoon prayer, but then we decided for the sunset prayer and the night prayer, we was going to make them in the gym. One of the brothers got on the bullhorn and said, “Look, Muslims are obligated to say five prayers a day; we got to get ready to say our sunset prayer, and we ask that everyone give us the respect that we would give them. We’re asking that they remain very quiet.”

And it was complete silence when we got to making our prayer. So after we got through with our prayer, we told people that we saw there’s some Christians, some Jews and people of other religious denominations, and if they want, to come down here in brotherhood and pray, because we don’t know what tomorrow holds. We don’t know what the next minute holds. We don’t know if these people gonna come in and storm this prison. We ask [from] everyone the same respect that you just gave the Muslims in being quiet.

The Christians got together, they prayed. Other people got together and prayed. People seen that there was really unity. And like I say, those were the two main turning points that brought about the concrete unity between Black and white.

Now from a Muslim perspective, we didn’t have any problem to begin with, because Islam negates racism. But you had the Aryan Brotherhood, [and] we had the Black Gangster Disciples — so that’s a white group and a Black group, but we was able to release the tension that was in the air. Which was a blessing.

MG: How and when did the rebellion come to an end?

IH: It came to an end on April 21. It started on April 11, Easter Sunday. There was various different factors. We was always trying to negotiate with the prison authorities in good faith, but they was trying to use stall tactics. They have a riot negotiation manual. Not only prison authorities have it; other establishments, police, FBI, they all have it.

One of their things is to try to delay, not allow [those in revolt] to talk to the leadership [of the authorities]. They was going to avoid us talking to the warden, because if the warden tell [the prisoners] “no,” they see they have no other outlet. So they would give you one of his subordinates. They keep giving you the runaround.

We negotiated for some type of deal: surrender. For a live television interview, we would give them one hostage. Then they come back and say, no, we want two hostages. So we felt they was trying to procrastinate, trying to stall and trying to find a way to actually storm the prison and retake it back by force.

So finally we was successful in getting a live radio interview. George Skatzes was the one who conducted that in the recreation yards, and then after that a Muslim brother, Stanley Cummings, went out with Channel 10 from Columbus — went out on the recreation yard. So we was getting close to [winding] down, and then the prison authorities got to stalling, and prisoners was saying [the authorities] were under no obligation to honor our demands, etc., [that] they might try to renege.

So a couple more days was stalled, and we got an attorney, Niki Schwartz, who is a Jewish attorney out of Cleveland, Ohio, who used to be with the ACLU and went on to private practice and handled a very successful case. He had a very good reputation in the prison system, because he was the one who forced the prison authorities to close Ohio State Reformatory, which was in Mansfield, Ohio. So he was requested.

He came to the prison and we talked to him — myself; Jason Robb, who was representing the Aryan Brotherhood; and Anthony Lavelle who was a representative from the Black Gangster Disciples. We drank coffee together, had a very cordial relationship, and we drafted what is referred to as the 21-point agreement. Niki Schwartz was instrumental in helping us to bring about a peaceful surrender to the unfortunate situation.

MG: So did the authorities agree to the 21 points?

IH: When we say agree, they used vague language. We would look at the medical treatment of prisoners. There was prisoners who’d been housed at Lucasville [whose] security [level] hadn’t been dropped. They should have not been in a maximum security prison; they should have been transferred out of Lucasville.

We would talk to the medical establishment, and we would see what could be done with regards to the TB test. [There were] only a few things [to which] they gave an exact answer. But Niki Schwartz went to them, and he was talking to the prison authorities, [who were] speaking for the governor.

He said, “If you’re not going to honor this 21-point agreement, then make it known to me now, and I will just turn away and walk from this.” And the governor explained to Niki Schwartz their intentions of fulfilling the 21-point agreement to the best of his knowledge, beliefs and ability.

Niki conveyed that to us. We trusted and believed in Niki and we decided to bring it to a peaceful surrender.

MG: How much of what they agreed to, did they live up to and have they lived up to over the past 25 years?

IH: Part of the 21-point agreement: that no inmate or group of inmates would be singled out for retaliatory action; that was not the case. At the conclusion of the riot, some of us who stepped up and became spokesmen for trying to bring the thing to a peaceful surrender — who were seen by the prisoners as people that can be trusted; their word is their bond — we came to be singled out.

During the initial part of the disturbance, the prison authorities went to some who were snitches: “Well, look, we don’t care about these other persons; what do you know about Imam Hasan? We want to know something on him.” And they were pushing words into peoples’ mouths, knowing that prisoners would basically say anything and everything they wanted them to say, because they can get transferred to one of these low-security prisons, out of Lucasville, which was a hostile environment.

[We were] transferred to some of the most harshest institutions in Ohio. For example, 129 of us were transferred to Mansfield Correctional Institution. [Later] myself, George Skatzes and Anthony Lavelle, we were transferred to Chillicothe Correctional Institution, what is referred to as the North Hole. It’s like a place semi underground in a dungeon behind two doors.

Jason Robb and the Muslim brother, who went out in the yard and gave a speech, Stanley Cummings, was transferred to Lebanon Correctional Institution, and that was not by coincidence. Jason Robb, Anthony Lavelle and myself, we was the spokespersons who worked with Niki Schwartz to bring about a peaceful surrender.

George Skatzes was the one who went in the yard and gave the live radio interview. Stanley Cummings was the one who went in the yard and gave the live interview to Channel 10 News. So it was by prior calculation and design that we were rode out to other institutions with more harsher conditions.

When it came to the prosecution of the case, the state was in cahoots with the prosecutor in committing prosecutorial misconduct and making sure that we were the ones, whether they had the evidence or not, that was actually indicted for the more serious offense.

Another part of the retaliation [was that] some prisoners was physically jumped on by prison authorities when they got the opportunity to do so. On Sept. 5, 1997, in Mansfield Correctional Institution, there was an uprising in the death row area. They came inside, and they jumped on George Skatzes. They jumped on Jason Robb, bust his head open, hit him on the head with a sledgehammer. I think he received at least 37 stitches.

MG: How many were framed up after the rebellion?

IH: You had 50 indictments. I think the state ended up with 49 or 48 convictions. A lot of those people pleaded guilty; some I’m sure because they actually committed the crime. Others pleaded guilty, because they were in a “Catch-22.” Their cases were being held in Scioto County, the county which the Southern Ohio Correctional Facility is in.

The whole entire community was affected by the uprising, and I don’t care what kind of evidence you have — tangible evidence, forensic evidence, scientific evidence — it didn’t make any difference. If you went to trial in Scioto County, you were not going to get a “not guilty” [verdict]. At best you might get a hung jury.

But in almost all cases, people knew they were going to be found guilty. Less than two dozen, maybe 16 or 18 people, actually went to trial. Most people knew that they didn’t stand a chance, so they went ahead and took the lesser of two evils. One evil [was] they could go to trial, be found guilty, be given the maximum sentences. Or they could plead guilty — an innocent man given more time, but it would be less time [than if they went to trial] — so a lot of people chose the lesser of two evils, because they saw they didn’t have a chance of winning their cases.

Perhaps only two who got convicted were actually released, and they were released because they actually maxed out on their sentences. You got to remember it is the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation Corrections director who appoints the parole board, and it would be akin to political suicide for them to grant one of the Lucasville defendants parole.

No one thinks when they go to the parole board they’re going to get any meaningful results. Most of them have been model prisoners, and they’re still locked up. But you do have some that was given 5 to 25 years, and this is the 25th anniversary, so the majority of them will be maxing out some time during this year, because [they] cannot hold them any longer than 25 years.

James Bell Jr. died in prison. And the person [who] went outside in the yard to give a live television interview, Stanley Cummings, died in Leavenworth, Kansas, in a federal prison.