Traditions of health: Black midwives and doulas against racism

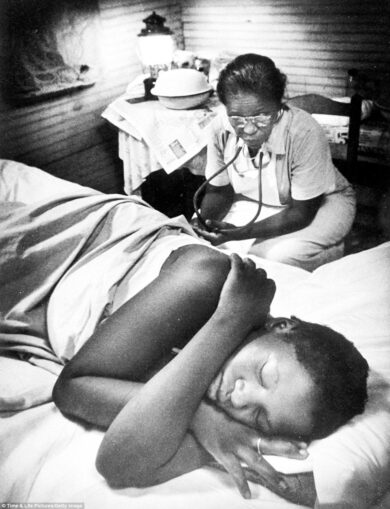

A Black midwife delivering a baby in the 1950s in the rural South.

Midwifery on the African continent can be traced back to antiquity. The tombs of queens in Africa depict midwives assisting at the births of royalty. This is significant because it indicates midwives were held in the highest regard. Given the gender structure of ancient African societies, it would be women, not men, who practiced midwifery. These women would be educated and quite possibly able to read and write. The Kahun papyrus is an African gynecological text dating back to 1800 BCE. It is the oldest known document of gynecological concepts. There is even archaeological proof that ancient Africans used spermicidal plants for contraception.

Midwifery after enslavement

Midwives of African descent enslaved in the Southern states were not permitted to learn how to read or write. This necessitated their passing on expertise orally to the next generation of Black midwives. In this oral form, their body of midwifery knowledge was misconstrued as folk remedies or, worse, witchcraft instead of the science that it was.

By the 1740s chattel slavery existed in every North American colony; but after 1808, the importation of people for enslavement was prohibited by U.S. law. The practice of increasing the number of enslaved people for sale through rape and forced pregnancy became an economic incentive.

As a result of this diabolical development, the enslaved midwife was valued by the slave owner. Additionally, enslaved Black midwives, because of their child-birthing knowledge, often assisted at the births of white women.

Plantation owner and enslaver George Washington valued the Black midwife so much that he was willing to pay her. “In February 1776, Washington paid the enslaved woman Jane, who belonged to Penelope French, for delivering one of his enslaved women at Dogue Run Farm. In April 1783, Washington paid ‘Mrs Frenches Negroe Woman’ for delivering ‘Doll’ at Ferry Plantation. Washington paid ten shillings for each delivery, and they were both recorded in the cash accounts. The payments went directly to the enslaved woman . . .” (tinyurl.com/4y228kfj)

Midwifery and the medical establishment

Up until the 20th century, home births were the norm for the majority of women of color and immigrant women in the U.S. Midwives assisted the mothers through the labor phase and birthing. This began to change, in part, after women’s suffrage.

White middle- and upper-class women flexed their new political muscle through the U.S. Children’s Bureau and campaigned for passage of the Sheppard-Towner Act. This 1921 law was instrumental in medicalizing pregnancy and childbirth. Some 3,000 child and maternal health clinics were established across the country during the eight years the act was in effect.

On the surface, it was considered a valiant attempt to reduce infant mortality by providing medical care to mostly poor rural communities. However, the act made no provisions for eliminating underlying poverty.

The Sheppard-Towner Act ended up negatively impacting Black midwives in the South, who were maligned as a common denominator for infant mortality in their communities. Black lay midwives were mandated to attend classes and be certified as “safe” practitioners.

Capitalists found a new source of revenue through the adoption of the medical establishment model for pregnancy and childbirth. But the history of U.S. gynecology is linked to the Black women who suffered torture at the hands of a medical profession doing “scientific research” based on racist assumptions. Most notably, James Marion Sims experimented with various new gynecological surgical procedures by performing them on unanesthetized enslaved Black women.

In a 1952 Georgia Department of Health film, Mary Cooley, a Black lay midwife, narrates her typical work week. “All My Babies,” and Mary Cooley became well known for the film’s accurate depiction of midwifery. But one scene shows a white doctor chiding a group of Black midwives about their lack of cleanliness. (tinyurl.com/bdhaa94e)

Black midwives and public health nurses

The Tuskegee School of Nurse Midwifery in Alabama was one of a handful of schools to teach midwifery to Black public health nurses. The school, established in 1941, was separate from the historic Tuskegee Institute, founded by Booker T. Washington, but used some of its facilities. It was under the direction of the U.S. Children’s Bureau and the Alabama Department of Health.

The premise for the school was that Black women of childbearing age would accept care from Black public health nurses, trained as nurse-midwives, more readily than from white doctors. Nursing education was mostly racially segregated, and Black women were excluded from attending most schools of nursing. The National Association of Black Graduate Nurses reported in 1943 there were 23 Black nursing schools but only 15 nursing schools that admitted both white and Black students.

The Tuskegee School of Nurse Midwifery was in operation until 1946 and graduated 31 Black nurse midwives. The accomplishment of these women in reducing the Black infant mortality rate is exemplary, considering segregation and other racist practices of 20th century health care.

Black people were often excluded from hospitals serving a white clientele. Hospitals for Black people were inadequately equipped and staffed. In 1941 there were just 110 Black hospitals — serving a Black population in the U.S. close to 14 million. Most of the hospitals were in urban areas, so Black rural populations were even further underserved.

The U.S. Public Health Department statistics for infant mortality in 1946 for Black infants was 74 deaths per 1,000 births, contrasted with 43 deaths per 1,000 births for white infants. The maternal mortality rate for Black people was three times higher than for white mothers.

The Tuskegee nurse midwives worked alongside the Black lay midwives and taught classes required under the Sheppard-Towner Act for lay midwife certification. Despite the ever present root causes of systemic racism, there was a noticeable decrease in Black infant mortality credited to the Tuskegee nurse midwives. Unfortunately, poor working conditions and underfunding forced the school to close after only five years.

Racial disparity in infant mortality today

The infant mortality rate signifies the likelihood that a newborn will die before they are a year old. It is a grim and heart-wrenching statistic.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services cites the overall rate of infant mortality in 2018 in the U.S. as 5.7 infant deaths per 1,000 births. However, Black infants were over two times more likely to die, at 10.8 deaths per 1,000 births, than their white counterparts.

Additional racial disparities surrounding maternal-child health include these facts: Black infants are four times as likely to die because of low birth weight complications. They are twice as likely to succumb to sudden infant death syndrome than white infants. Black mothers were twice as likely to receive late or no prenatal care as white women. (tinyurl.com/eaabhzw) Prenatal care is a widely recognized necessity for screening expectant mothers early for potential health problems that may complicate either the pregnancy or the birth process.

From the tortures of enslavement to the Jim Crow era of segregated hospitals to the current underfunding of social services and health care in Black communities, the U.S. state and individual state governments have institutionalized the oppression of Black people regardless of their vulnerability or tender age.

About 71% of children living in poverty are people of color. (tinyurl.com/2p9564yk) Food insecurity, inadequate housing, lack of safe water and poor air quality are consequences of poverty and negatively impact maternal-child health. These conditions could be eliminated, if resources were adequately provided rather than wasting them on imperialist warfare and lining the pockets of megacapitalists.

Instead for centuries the ruling class in power has propagated the racist myth that Black women are neglectful caregivers and therefore to blame for health disparities.

Lifting the stigma off Black mothers

There is a movement among progressive Black health care workers to debunk fallacies around Black motherhood, by acknowledging systemic racism as the root of the problem of health disparities.

Black nurse midwives and doulas cannot solve Black infant mortality, and that should not be the expectation. What they can provide to Black mothers is care and respect during their pregnancy and childbirth, while acknowledging their struggle within an oppressive system.

Dr. Michelle Drew is a nurse midwife, family nurse practitioner and director of the Ubuntu Black Family Wellness Collective in Delaware. Dr. Drew’s mother and grandmother are midwives, who trace their ancestry to an enslaved midwife.

The Ubuntu collective, established in 2019, pushes back the narrative blaming Black women for the racial disparity in infant mortality. Dr. Drew and her colleagues point to the systemic racism creating poverty and poor health care and inflicting harm on Black mothers and their infants as the root cause. (tinyurl.com/mrytn27e)

The Birth Sisters of Charlottesville, Virginia, provide guidance and support throughout pregnancy and childbirth, as well as postpartum and lactation support, for Black, Brown and Indigenous peoples in their city and surrounding counties. These doulas of color have shared experiences with the women in their care. They deny that race is a factor in infant and maternal mortality disparities. They point to dismantling systemic racism as a permanent solution. (tinyurl.com/bdf78uws)

The Peer Doula Program at Logan Correctional Center in Chicago pairs a trained incarcerated doula with an incarcerated pregnant person. The goal is to reduce the isolation and harm that incarceration has on mother and baby. (tinyurl.com/bdrp6mvm)

Recognizing the injustice and inhumanity of the carceral system and how it destroys families is a small step toward abolishing prisons and providing communities with the resources necessary to tackle the material conditions at the heart of Black infant mortality.

The tradition of Black midwives committed to the health of children and birthing mothers continues in the fight to dismantle systemic racist and gender oppression.

Ellen Cohen, a retired midwife, contributed to this article.