Devastation in retail points to deepening crisis in capitalist economy

Even after stock market prices dropped over 10 percent in three days, many corporate media pundits dismissed concerns over this volatility by pointing to an allegedly strong economy. The retail sector of that economy, however, is beginning to fracture, indicating a potentially widespread crisis.

Even after stock market prices dropped over 10 percent in three days, many corporate media pundits dismissed concerns over this volatility by pointing to an allegedly strong economy. The retail sector of that economy, however, is beginning to fracture, indicating a potentially widespread crisis.

The ‘Retail Apocalypse’

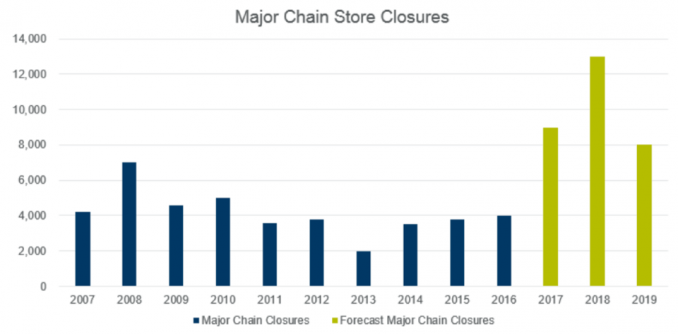

What experts are calling a “tsunami of store closings” is imposing “retail carnage” on the U.S. economy. More than 12,000 stores are expected to close in 2018 — on top of some 9,000 closed in 2017 — according to commercial real estate firm Cushman & Wakefield. (Business Insider, Jan. 1)

Retail bankruptcies are snowballing. Last year was “one of the most brutal in the industry’s history in terms of bankruptcy filings and store closings,” according to the Dec. 25 Fortune magazine. Some business commentators are warning of “a retail Ice Age.” (Fox News, July 11)

Dozens of major retailers have filed for bankruptcy in recent months, including Bon Ton, Toys ‘R’ Us, The Limited, Hhgregg, Radio Shack, Payless, True Religion, Vitamin World and Aerosoles. Other major chains, including Macy’s, J.C. Penney, Sears, The Gap, Banana Republic, Michael Kors and Kmart, have closed many stores.

An economic glut of empty retail stores now threatens the economy much like unpayable mortgages did a decade ago. Mall visits declined 50 percent between 2010 and 2013 and have fallen every year since. No new major shopping mall has opened in the U.S. during the past three years, and 50 percent of the existing 1,200 malls are expected to be out of business within five years.

The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta has warned about the exposure of financial institutions to these retail failures. Bonds backed by loans to malls and other retail properties are weakening. This recent and ongoing crisis even has its own entry in Wikipedia — “Retail Apocalypse.”

The Amazon onslaught

The collapse of so many retail stores, chains and malls is due in large part to the growing dominance of Amazon. In 2015, Amazon surpassed Walmart as the most valuable retailer in the U.S. In the last quarter of 2017, Amazon’s profits exceeded $1 billion for the first time. Daniel Ives, head of technology research at GBH Insights, estimated that 47 percent of all online holiday shopping took place on Amazon’s website. (CNN, Feb. 1)

Amazon started as an online bookstore and later expanded to sell a vast array of other products. It is now the largest seller of clothes online and will soon become the country’s biggest apparel retailer. It takes a percentage of the price of items sold through its website while also charging companies to advertise and feature their products.

Amazon obtained its dominant position by forgoing profits in its early years — aided by favorable bank financing arrangements — and prioritizing growth to establish large-scale sales. It slashed prices to drive out competition and spent billions to expand capacity and become a one-stop shop for consumers.

Amazon is not just an online business. Last year it acquired Whole Foods, a high-end supermarket chain with over 450 stores, for $13.4 billion. Amazon also owns brick-and-mortar bookstores and, according to some venture capitalists, has its eye on purchasing Target, with its huge chain of discount department stores. (twice.com, Jan. 2)

Amazon also has its own product lines, ranging from clothing to furniture to baby wipes. It recently announced plans to enter the pharmaceutical market and to launch a package delivery service designed to take business from FedEx and UPS.

Amazon’s involvement in multiple related business lines means that many of its rivals are also its customers. Competing retailers often use its delivery services, and many competing companies use its platform or cloud infrastructure. These arrangements enable Amazon to favor its own products over those of competitors.

These interactions also capture market data that get fed into algorithms — computer programs that process this raw data involving the customers’ choices and provide Amazon with additional competitive sales advantages that increase its dominance. And with dominance, Amazon has the power to increase prices, reversing its initial position as a discounter.

Amazon and Walmart’s domination of retail commerce goes far to explain the devastation they and others like them have wrought in the traditional retail marketplace.

Replacing workers with technology

According to last June 16’s New York Times, Amazon “is on a collision course with Walmart to try to be the predominant seller of pretty much everything you buy.” This market domination by retail giants does not simply reflect the shift to online shopping. As noted above, Amazon’s brick-and-mortar businesses are growing, and Walmart, which increased its online sales 50 percent last year, operates 4,000 stores.

This domination also reflects an enormous concentration and centralization of capital in the retail sector. Vast accumulations of capital in fewer and fewer hands — including those of enormously wealthy capitalists like Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos — have been a feature of capitalism since Karl Marx described its workings 150 years ago.

What is new is that this tendency toward monopoly is no longer limited to the production side but is now taking over the retail sector as well. This development is already having a profound impact on the U.S. economy and U.S. workers. The retail sector lost over 100,000 jobs in 2017.

Retail jobs face the axe not just from closing stores but also from the competitive compulsion to replace workers with technology. Recent studies show that a majority of the eight million retail salespersons and cashiers in the U.S. workforce face job elimination by advanced technology. And high tech is also displacing warehouse and distribution center workers, with Black, Brown and women workers generally the first to lose out.

Amazon recently opened its first cashierless convenience store in Seattle. It uses an array of sensors and cameras to charge shoppers automatically for items taken from shelves. As Bloomberg News put it last June 16, Amazon “wants fewer employees in each store.”

This developing technology, in which only retail giants like Amazon can afford to invest, will lead to enormous job losses. Movie theater chains, where online ticket sales have significantly reduced staff, already offer a preview. And employing workers who simply service technology allows employers to reduce wage rates.

This job and wage destruction is perhaps the primary product of the quasi-robotic, mostly part-time labor, anti-union Amazon leviathan. Replacing retail workers with sensors and robots will reduce employment and lower wages for those able to find work. It will ultimately reduce sales as the buying capacity of unemployed and underpaid workers sinks.

To be sure, Amazon’s online and retail businesses require giant distribution warehouses that house large concentrations of workers. But Amazon’s warehouse pay scales are low and declining and tend to cause a reduction in wages at neighboring employers. A recent study found that ten percent of Amazon employees in Ohio are on food stamps.

What’s more, these warehouse jobs are grueling and high-stress and often seasonal or temporary. A reporter who visited several warehouses found that “Amazon puts an incredible amount of pressure on people to continue to work faster and faster.” (Atlantic, Feb. 1) It should be no surprise then that Amazon recently patented a wristband that ultrasonically tracks every move made by its workers, perhaps the ultimate in control technology.

The other side of massing workers in huge warehouses is that it will enable workers to share and discuss the details of their exploitation, learn how essential their role is to the realization of profit and obtain a sense of their formidable power. They can then plan collective resistance and rebellion.

Stock market volatility may continue, or the markets may stabilize for a time. But the march of the most powerful high-tech companies toward retail dominance will proceed and wreak economic havoc until it is stopped in its tracks by its victims and ultimate victors — the workers and oppressed. As Marx explained in “The Communist Manifesto,” the insatiable pursuit of profits by the boss class inevitably produces “its own gravediggers.”