No cop city! Battle for the Atlanta forest not over

Let me tell you the story about how a small group of wealthy and powerful corporate leaders, known as the Atlanta Police Foundation, grabbed city-owned, heavily forested park land for a massive police urban-warfare training center.

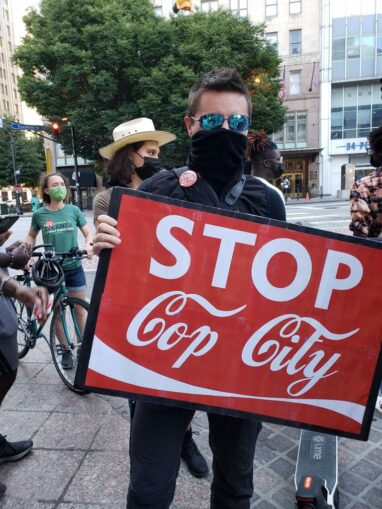

Atlanta protest at Coca-Cola museum, Sept. 3.

Much of the wheeling and dealing occurred in secret with the proposal only made public June 7, when Atlanta City Council member Joyce Shepherd introduced the “Cop City” ordinance. It authorized a 50-year lease of 381 acres of previously designated green space at $10 a year to the private Atlanta Police Foundation to build a $90-million police training facility.

Neighboring communities of mostly Black and low-income residents on the southside of Atlanta were shocked and horrified to learn that there would be multiple gun ranges, areas for deploying explosive devices like tear gas, flash-bangs and other toxic weapons.

The plan included a helicopter port, a tactical driving course and a mock city, complete with apartment buildings, stores and a gas station where crowd control, surveillance and SWAT-style tactics would be perfected. Plus a burning tower where firefighters would train. In addition, classroom buildings, dorms and lots of concrete parking lots. The plan would require the cutting down of thousands of substantial trees, cutting down of the forest itself.

If some alert organizations and individuals had not been paying attention to the goings-on at Atlanta’s finance committee meetings, this theft of public land could have been accomplished easily. The Police Foundation leadership from Delta, Home Depot, Coca Cola and Cox Enterprises, owner of the Atlanta Journal Constitution, certainly never intended to engage the public.

Fortunately what happened was an explosion of organized resistance that started small — mostly by politically and environmentally conscious youth — but grew into a large, vocal opposition that forced repeated delays in a final Council vote. Every nearby neighborhood association, environmental and conservation groups, radical youth, left political organizations, legal experts and community groups focused on prison conditions, voting, gentrification, education and youth services had a hand in mobilizing opposition.

City Council meetings are held virtually, so hours and hours of recorded public comments, upwards of 17 to 20 hours, heavily opposed to the “Cop City,” had to be played. Some of the small minority who supported the proposal lived in Buckhead, an extremely rich area on Atlanta’s northside. Their repeated reason for supporting “Cop City” was to stop the increase in violence and property crime in their neighborhood, even though the facility would not be operational for a few years.

Potential of more repression, environmental disaster

Some opponents raised the destruction and erasure of the remnants of the historic Old Atlanta Prison Farm, where for decades mostly Black incarcerated workers labored under brutal Jim Crow segregation conditions to produce food for others.

Others cited the potential devastating damage by heavy metals from exploded armaments to the air and water quality of Entrenchment Creek and the South River. Both waterways run through the area and are necessary to waterfowl and other wildlife.

Many disputed any notion that the militarized techniques wouldn’t be primarily used on people of color, particularly youth. It was not lost on DeKalb County residents that the land in question was in unincorporated DeKalb County, so they had no say about what Atlanta would do with it. In another glaring legal contradiction, the whole forest had been designated as a green space in perpetuity by a 2017 City Council ordinance.

In a heavily bankrolled public relations campaign, the Police Foundation declared that the training facility was key to “making Atlanta safe” by raising the morale of police and making recruiting additional members easier. It downplayed all the training of military-style weaponry and counterinsurgency tactics by saying the academy would be named the “Institute of Social Justice.”

Like many cities, Atlanta saw large continuous demonstrations following the videoed murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police, in the summer of 2020, and again when police killed Rayshard Brooks in a southside neighborhood of Atlanta. Large numbers of protesters were arrested; tear gas and clubs were used to disperse marchers.

Efforts to redirect city funding from police budgets to mental health services, affordable housing or job training were defeated by the same Council members who a year later voted to support Cop City with an anticipated $30-million portion to be paid out of tax dollars. Ignoring the overwhelming community opposition to the urban warfare training center, on Sept. 8 the Atlanta City Council voted 10 to 4 to approve the ordinance.

Many of the organization members who had canvassed door to door in the adjacent neighborhoods, held numerous demonstrations, organized public meetings, distributed thousands of leaflets and lawn signs and phonebanked were, of course, disappointed and angry but also determined that the fight is not over.

It is likely that lawsuits will be filed, and environmental studies remain to be done before construction can begin. Other direct actions are contemplated. Moreover, every City Council seat is up for election in November, as well as the mayor’s office. The Sept. 8 decision could be reversed if popular pressure can be maintained and expanded.

The story to STOP COP CITY is not over. The fight to abolish the racist enforcers of class rule is on. Will you join?

Photo Credit: Gloria Tatum