Cuban unions build socialism

Member, Communication Workers Local 14156

What are the differences between unions in capitalist countries and socialist countries? What is labor’s role in a socialist country? I first became a supporter of socialist Cuba as a labor activist in the San Francisco Bay Area, and I learned about Cuba’s unions in the course of two trips to Cuba, 27 years apart.

In 1992, I joined a group of 22 members of over a dozen U.S. unions for the U.S.-Cuba Labor Exchange’s second trip. As guests of the Confederation of Cuban Workers (CTC), we visited all manner of workplaces — factories, ports, agricultural projects, hospitals, clinics and schools. We met with many Cuban union members and leaders. And we had most evenings free to explore Havana!

Our visit was during the Special Period, when Cuba lost 85% of its trade as a consequence of the fall of the Soviet Union and Eastern European socialist countries. Cuba had to make do with less than half its usual oil supply.

Many shortages resulted as the U.S. intensified its economic war on Cuba’s ability to sell its nickel ore, sugar cane and other agricultural products. Cubans made up shortages of some foodstuffs with what was available, in order to ensure adequate nutrition. In 1992, Cuba was selling its entire lobster catch to buy milk for first-grade children.

CTC Secretariat member Joaquin Bernal Camero told us: “You will never find a Cuban union leader asking for privatization of enterprise. We’re not going to give back the land to the former landowners or corporations. Our unions are independent, but also independent of the capitalists. We don’t take a coin from the government, and all the dues collected go back into the union work.”

Membership is voluntary, yet we found out that 97% of Cuban workers belonged to unions, which are entirely self-financed from dues. Cuban unionists enact their own laws and constitutions. The rank and file directly nominate and elect their own leaderships in a regular series of elections far outnumbering those of other countries.

We learned Cuba had free health care and free or affordable daycare, and rents were limited to 10% of income. Women had three months paid leave before giving birth, six months paid leave afterward and the right to return to their jobs. (Parental leave was later extended to fathers.)

The CTC reviews all new laws before they are enacted, and labor law has workers’ rights at its center. In a joint-venture hotel with Spain, the workers voted out three managers in a row before they got one who complied with Cuban labor law.

But in 1992 what most impressed me — coming from white-supremacist U.S. during the Rodney King Rebellion — was the deep respect the working people displayed toward each other and the kindnesses we visiting unionists experienced.

Our final workplace visit was to the H. Uppmann tobacco factory. The workers told us they worked six months, then took a month’s vacation. Windows were wide open while they worked with their hands, some singing, others smoking — I could be happy working there!

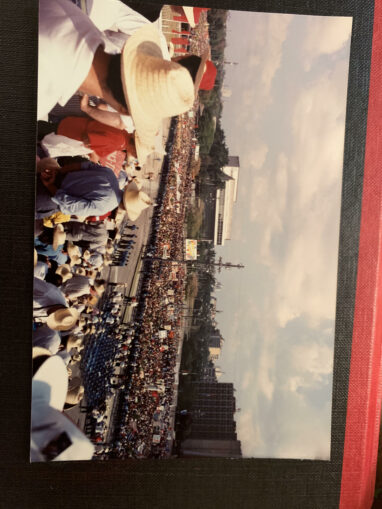

May Day, Havana, 1992

WW Photo: Stephanie Hedgecoke

Going back to Cuba

In the Special Period, Cuba increased resources and built up its biopharmaceutical and tourism industries. But in 2019 former President Donald Trump invoked Title III of the Helms Burton Act, further increasing the illegal blockade’s economic strangulation, threatening the working people.

I returned in summer 2019 with the 50th Venceremos Brigade, which travels in solidarity with the Revolution to contribute materially to it. The day after we arrived, we toured Las Terrazas in the Sierra del Rosario region, where in 1968 local villagers created a reforestation plan with support from the revolutionary government.

Within eight years, the rural people in the valley had planted 6 million trees in an area totally denuded during Spanish colonization. Over 80% of the food eaten in the biosphere is locally grown, all organic. Some 7 million indigenous trees have now been planted; biodiversity of flora and fauna has recovered. In 1985, the U.N. Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization recognized the first Biosphere Reserve in Cuba.

Our guide Ida explained the impacts of global warming. Some varieties of plants have disappeared from the forest due to the heat; others are in season earlier and longer, like mangoes. The past average year-round temperature in Cuba was 75 to 77°F; in 2019 they had a new high of 103.64°F.

The next day, the Brigade sent me to work in a lime orchard to clear invasive vines choking the trees. Afterward, the local workers regaled us with a fiery recounting of historic Cuban freedom fighters on horseback, machetes in both hands, terrifying the Spanish overlords!

Later that week, several Brigadistas gathered in the camp library to hear Ismael Drullet Pérez, General Secretary of the National Union of Education, Science and Sports Workers, the largest Cuban union. Pérez said the CTC’s main mission is to represent the needs of the workers and their families before the state and society.

Ismael Drullet Pérez, General Secretary of the National Union of Education, Science and Sports Workers, Cuba’s largest union

Workers are active in the CTC at municipal, provincial and national levels. In a national survey, Cuban workers wanted the work of the CTC strengthened.

Although there was no single opinion, it was clear “all workers understood the continued need for their trade unions in the process of construction of our socialism.” Pérez emphasized, “the enemies of the Revolution lie that the CTC is under the government. But we were a union 20 years before the Revolution. The unions were strengthened with the coming of the Revolution.”

Cuban union members meet every two months to ask questions, to get answers — in each of the 19 sectoral unions, at every level. All managers are required to account for the budget, given from the government, to a general assembly of the workers. Union membership remains voluntary, with membership held by 95% of workers in the state sector and 65% of the workers in the private sector. And as we were visiting, the entire state sector had just received significant salary increases after economic studies by the CTC.

The increased blockade by the U.S. has shut down Cuba’s ability to obtain machinery parts from overseas. Pérez said, “Our factories are old; our machinery needs parts and frequently breaks down. We keep them running through the creativity of the workers solving the problems. But we won’t accept the loss of our independence, our social justice and equity. We are not paradise, and we are not hell.”

Brigadistas asked about the private sector and what role unions have with prisoners. As blockade-imposed hardships resulted in some turning to crime, Pérez said the CTC represents those who were arrested for petty crimes of corruption; “insertados” have representation to help them transition to get work.

The CTC still has final say over new laws; workers in joint ventures can still vote out hostile managers. Pérez noted, “The Labor Code of Cuba regulates all joint ventures and private employers. Problems that come from the past we reshape and eliminate. We accept the workers as they are.”

The CTC sometimes intervenes with small employers in the private sector; for example, in one case the union had to enforce labor law against gender discrimination in restaurant work. Pérez emphasized: “We are working on this issue on an inherited legacy of slavery and colonialism — hundreds of years of colonialism vs. 60 years of revolution.”

During the COVID pandemic, tourism has taken an enormous hit. Yet Cuban science workers created their own vaccines. In 1992 Bernal Camero had said that during the Revolution, “Cuban workers occupied the factories.” Cuba’s unions continue to remain key to building socialism in that Caribbean island nation.