Incarcerees organize unprecedented seminar against life sentences

For some Pennsylvania state legislators, incarcerated people belong in prison, no questions asked. “Lock ’em up and throw away the key,” as the reactionary saying goes. State policies that sustain the mass incarceration of Black and Brown people and members of impoverished communities hinge on people not knowing the hidden lives and particular circumstances of incarcerated individuals, especially those sentenced to life without parole.

According to DecarceratePA, “Pennsylvania prisons currently hold approximately 5,100 people serving life sentences. In Pennsylvania, life means your natural life, with no possibility of parole. You receive mandatory Life Without Parole (LWOP) if you are convicted of first- or second-degree murder, even if you were only present at the incident and were not accused of being the person who pulled the trigger. Since these sentencing guidelines are mandatory, judges have no discretion in sentencing and cannot take into consideration any mitigating circumstances.” Pennsylvania is one of only six states that denies parole to lifers.

Because LWOP means sentencing people to die in prison, many people have come to call it “Death by Incarceration” (DBI) or “the other death penalty.” Life without parole sentencing is both immoral and expensive. It costs the state of Pennsylvania an average of $42,000 a year to incarcerate someone, but it costs approximately $66,000 a year to incarcerate elderly prisoners, due to higher medical costs. (tinyurl.com/3esxn97b)

LWOP disproportionately targets people of color. In Pennsylvania, people serving DBI sentences are 65% Black and 8.5% Latino. Pennsylvania also incarcerates the second-highest number of elderly prisoners of any state. Not everyone who is elderly in prison is serving LWOP, but many are. In 1980 there were 370 elderly people in the state prisons; now there are over 8,000.

Lifers organize vs repressive laws

Incarcerated people at State Correctional Institute (SCI) in Coal Township say they are more than just numbers. A group of incarcerated leaders there united last year under the idea that if state legislators and officials could meet and talk to those sentenced to LWOP, unfair repressive laws might be changed. Amazingly, from behind bars, they were able to organize an unprecedented gathering called “A Criminal Justice Reform/Lifers Seminar” on May 23 inside SCI Coal Township.

Thirty incarcerated people were allowed to meet for five hours with city and state officials, including State Sens. Shariff Street, Nikil Saval and Camera Bartolotta; Lt. Gov. Austin Davis, former Lt. Gov. Mark Singel, former state Speaker of the House Bill Deweese, SCI Coal Township Superintendent Tom McGinley and Montclair State University Professor Tarika Daftary Kapur. Guest speakers included Keir Bradford-Grey, former Chief Defender, Philadelphia Defender Association; Samuel Barlow, commuted from Life Without Parole; and Jamar Sowell, released from Juvenile Life Without Parole.

The organizers’ main goals were centered on several state legislative bills: geriatric compassionate release (HB587), sentencing and parole issues (SB135), parole due to age, illness and other reasons (SB136), and reducing commutation board votes from unanimous to 4 to 1.

No press or media were allowed to attend. This article is the first extensive report on the May 23 event. In addition to frequent Workers World contributor Bryant Arroyo, this newspaper interviewed five other incarcerated participants in the Seminar: Nyako Pippen, Derrick Cramer, Derrick Stevens, Dominick Serratore and Robert Pezzeca.

‘We should be judged for the totality of our life’

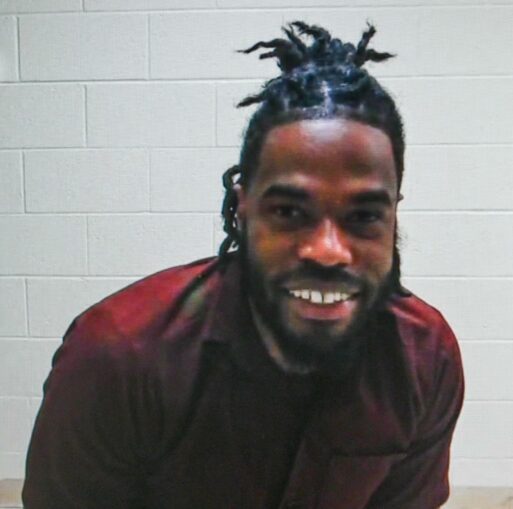

Nyako Pippen (WW Photo: Joe Piette)

Even though the U.S. Supreme Court recognized in 2012 that brain development continues until a juvenile’s mid-20s or later to reach maturity, it limited its ruling against juvenile life sentences to 18 years of age or younger. Pippen was 19 when arrested, convicted and sentenced to life in prison without chance of parole.

Workers World asked: Why should you and others be given a second chance? Excerpts from Pippen’s interview follow:

NP: “First and foremost, it is not lost on us the harm that we caused and the life that was lost. We acknowledge that, and with that acknowledgment comes responsibility. A lot of us have embraced the obligation to give back and make amends for the harm that we caused. Secondly, we still have value.

“It’s one horrible decision we made that led to us serving life without possibility of parole. And now after decades of hard work, even for some of the good work we’ve done before the crimes that were committed, I think we should be judged for the totality of our life, not just one or even multiple bad decisions.

“At the time of my arrest, I had only completed eighth grade. I grew up in impoverished conditions in a broken home, my mom and dad separated. We had addiction issues and homelessness in an unstable neighborhood — a harmful environment that influenced my thinking and formed the way I chose to survive. The combination of things contributed to my lack of focus at school, my lack of attention and my inability to discern appropriate life issues, which was survival at the time.

“My mom suffered from addiction, and my older brother was hospitalized, and my younger sister Anita suffered from cerebral palsy. We were evicted from our home, lived in a van for a while. At one point, we lived alongside a total of nine people in a one-bedroom apartment in Bristol, Pennsylvania. I adopted the idea early on to be a provider and take on responsibility — responsibility that, as a child, I was not prepared for and not equipped to handle. It was traumatic in a lot of ways.

“I think I’ve been able to reach the point where I can understand these issues. That’s one of my main motivators in trying to help people develop, to reach people here who grew up in similar impoverished situations, with the addictions that plague our communities.

“Since my conviction, I got my high school diploma and completed some secondary certificate programs in computer-aided design and drafting. I also did some correspondence courses in creative writing and entered multiple programs. A former professor from Bucknell University comes in, and we enhance our critical and analytical thinking. Obviously if you have better thinking skills, you will make better decisions, and it’s all tied together.

“I used to think praise and respect was earned through violence, that money was equivalent to success. Now I understand it’s about humanity. It’s about relationships. It’s about us working together and not harming each other. That’s where you get success. Money is secondary. Money is just a means of exchange.”

‘Felony murder’ rule = death by incarceration

Pippen was convicted of second-degree murder. Even though he didn’t kill anyone, he was part of a group of six people who planned a crime that resulted in a murder. In Pennsylvania, the felony murder rule under those circumstances stipulates an automatic life sentence without parole.

NP: “Reforming the felony murder rule was discussed during the May 23 Seminar, but that’s not what my speech was about. I spoke on our acknowledgment of the harm we caused from our crimes. Once we understand the obligations from that understanding, we have the responsibility to not only never repeat that harm but also to prevent other people from being victimized. I spoke genuinely with passion, from the heart. It was received well. Everybody appreciated it — some people were crying.

“Before me, Professor Kapur, three legislators and the lieutenant governor spoke. I was followed by Pezzeca, Cramer and Arroyo. Then we all broke off into small group discussions consisting of four topics: victim advocacy and empathy; life without the possibility of parole; compassionate relief; and commutation.

“This was my first time doing any public speaking. I got choked up at the beginning, but I was able to collect my thoughts. Everybody said I did a good job. Now I’m obligated to do it again. It’s for our freedom and the broader humanity.”

With determination, building the seminar

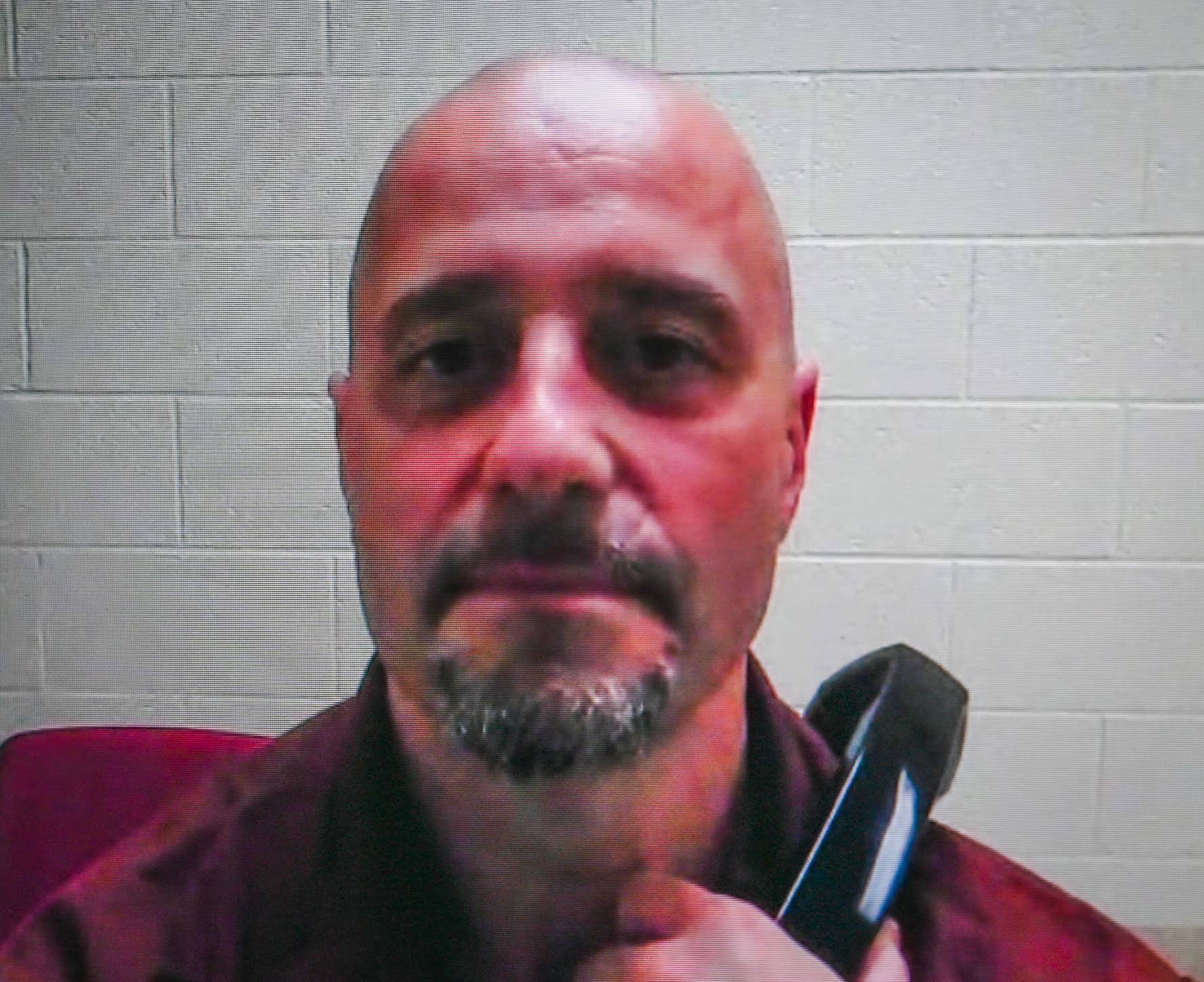

Robert Pezzeca (WW Photo: Joe Piette)

RP: “After seventh grade I just started getting into trouble and stopped going to school, and then I went to juvenile jail. . . . This was in New Jersey, notorious at the time for having extremely violent juvenile facilities. And these are the types of places that just made you a worse human being. The time in your life when you’re being molded into becoming an adult. I was being molded into becoming a violent teenager.”

Both his parents worked, but “we still grew up in poor sections of Bucks County and Philadelphia. And it wasn’t an easy upbringing. But my parents did the best they could. Sadly, they were both addicted to drugs.”

WW: Should you and incarcerated people serving life without parole get a second chance?

RP: “I’m a child survivor of sexual abuse. And back in the ’80s, no one cared about that. So for me until I got past that, I wasn’t able to grow up mentally. Physically, sure, but mentally and emotionally — no. I was not a good child. I was not a good teenager. I wasn’t a good person, period.

RP: “But 25 years later, I’ve grown to become a really good person. I’ve done some really good things in prison. I’m trying to show society we have changed; many of us have changed. I didn’t plan to commit my crime. I am absolutely guilty of it though. I didn’t plan it. I did not want it to happen. But it happened, and this isn’t the movies or TV — I can’t take it back. All I can do is try to show that I owe a debt to society. I took something from the world that should not have been taken — a person’s life.

“I made a horrible choice that night. I’m doing everything that I can do to atone for my crime. I can’t wash the blood away. But I can try and make up for it. And that’s the thing I’ve been trying to do for at least the last 10 years. I am in no way perfect. I make a lot of mistakes here. But hurting someone is not something I’ll ever repeat.”

The May 23 seminar was Pezzeca’s idea. After getting the permission and cooperation of SCI Coal Township Superintendent Tom McGinley, Pezzeca and another lifer Derrick Stevens eventually put together a list of 30 lifers “who had transformed” to participate in the proposed event.

With the help of his partner Kathleen and sister Jen, and co-organizer Stevens’ relatives, they spent five months sending hundreds of letters and making many phone calls to legislators, officials and others to attend the event. Finally, they chose a date and got permission from the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections (PA DOC) central office.

SB-135 would open up parole to lifers

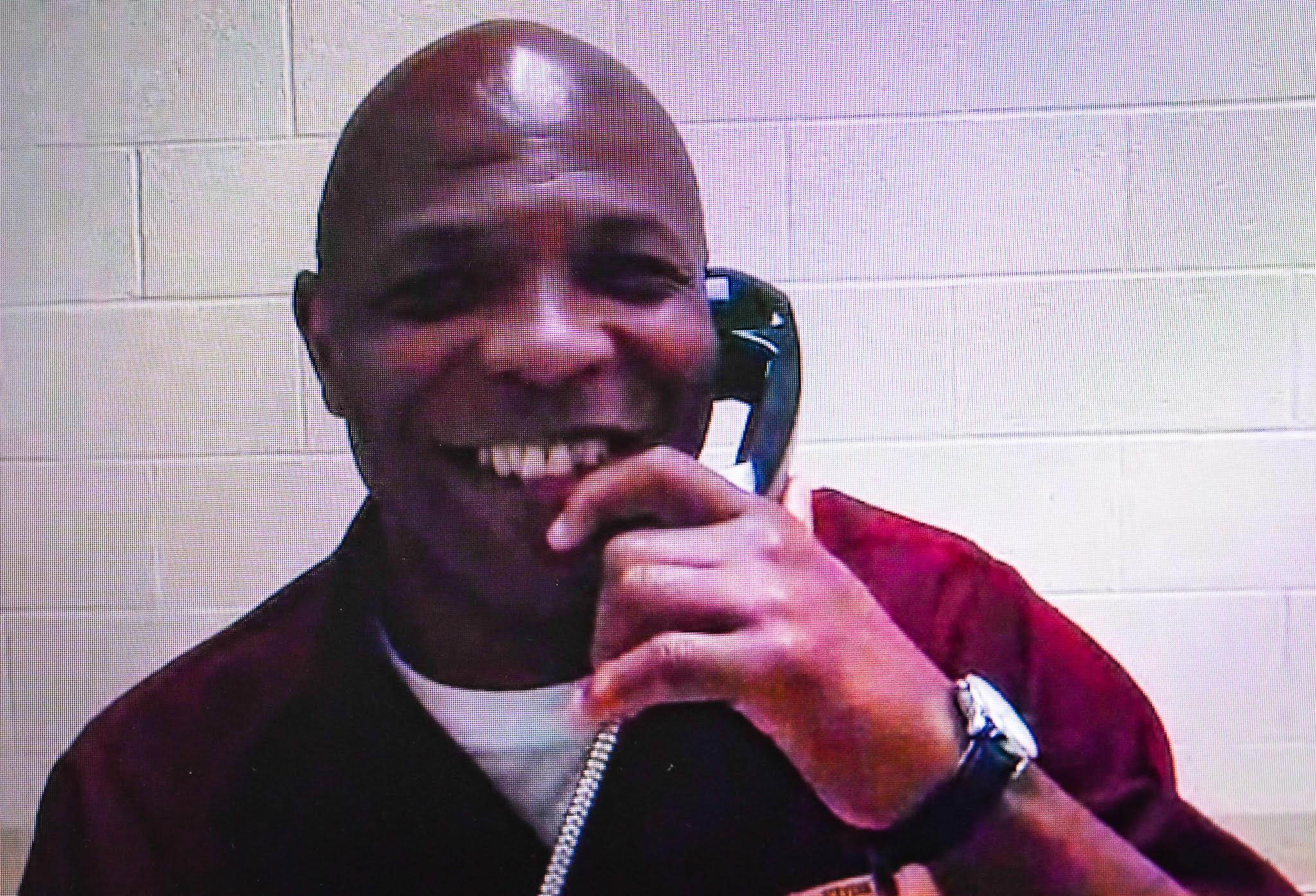

Derrick Stevens (WW Photo: Joe Piette)

WW: Should you and other incarcerated people serving life without parole get a second chance?

DS: “ I was able to obtain my GED in prison. I’ve learned communication and so many other skills. I’m a Certified Peer Specialist; that’s my job in here. I help my peers with their challenges and their stress when it comes to mental health. I think my nature is to help people. We just completed a course through Bucknell University on science and technology.

“If you ask the staff, they will tell you lifers are the most model prisoners. We are the mentors. We are the ones who give back to the community. In the last 10 years, lifers here have raised over $100,000 for various community causes. Lifers increase their education, even though in Pennsylvania, not more than 10% of lifers are allowed to enroll in academic, vocational or treatment programs.

“These are some of the issues we wanted to discuss with officials on May 23. We wanted to talk about alternatives to life without parole, about the impact our crimes have made on our victims, their families, communities and society as a whole. We had victims’ advocates come in, because we wanted to build a bridge with them. We wanted to show remorse. We wanted to be more productive and helpful when it comes to victims’ families.”

Stevens described the provisions of proposed SB 135, which would open up the possibility of parole for many lifers.

DS: “SB135’s criteria allows those convicted of second-degree murder to be paroled after 25 years behind bars after reaching 55 years of age. For first-degree murder convictions, they must be incarcerated 35 years and be at least 55 years old to be eligible for parole. Other rules include a good prison record, paid restitution and at least one academic achievement. You are ineligible for parole if the conviction involved the murder of a law enforcement official or someone under 18.”

Stevens says what he’s learned over the years can be summed up in three points.

DS: “The older generation taught me we need education. Most of us coming into prison don’t know who we are or where we come from. Secondly, we can’t judge everybody by their looks. Lastly, never give up hope.”

Education and jobs, not prison!

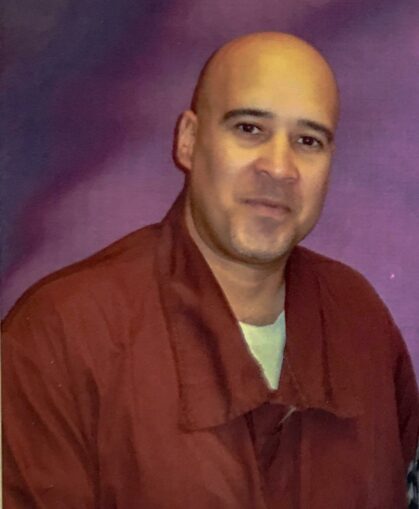

Derrick Cramer (WW Photo: Joe Piette)

DC: “Other guys have been here a lot longer than me. I wake up every day, and I see some of these guys around here still pushing forward and going to the law library to fight their cases. I mean, it’s hard. It is hard to do that every day after you’ve been told no so many times — it’s really hard.”

WW: “Why do you deserve a second chance?”

DC: “We don’t believe we deserve anything, but we’re trying to change people’s ideas of who we are today. We spend time every day trying to atone for what we did.I dropped out of school in 11th grade, because I was more worried about drugs and drinking. Now I’ve got my GED. I’ve become very educated. I completed National Center for Construction Education and Research (NCCR) Core level one, level two and HVAC (Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning) courses.

“I’ve gotten three job certifications through Ferris State University for the HVAC industry. And I have my EPA certifications for HVAC. I’m a tutor in the HVAC vocational school now. I mentor other guys, and older guys mentor me.

“I just don’t think the same as I did when I was 24 years old. You look back, then you took everything for granted, and now you don’t take anything for granted. I try to better myself somehow each day, learn something, try to help somebody else if I can. When I was younger, that was never part of my thinking.

“I was very addicted to drugs and alcohol. I don’t say that as an excuse, but since that day I haven’t touched drugs or alcohol and never would again, knowing what I did to my family and somebody else’s family by taking away a loved one from them. I made the commitment that I would never put myself in that situation ever again.

“We organized that seminar to let people see who we are today — that we’re not who we were 23 years ago. It’s like a snapshot, a picture of you when you went to jail, when they hear your name, that’s what they think about: “Oh, yeah, he committed murder.” They don’t think about 23 years later — what I am right now.”

An eight-member panel supervised the release of over 300 juvenile lifers following a U.S. Supreme Court ruling. It resulted in an extremely low recidivism rate of 2%. (tinyurl.com/4zfsaxty) Cramer thinks a similar panel could be created when a new bill is passed that would handle the thousands of lifers who would be eligible for a second chance.

DC: “ Gov. Shapiro’s budget for the PA DOC will be almost $3 billion this year. That’s a big chunk of money for a system that has a 60% recidivism rate! That’s a failing business.” [Comparatively, Cramer is pointing out the 2% recidivism rate of lifers after release.]

DC: [To lower the recidivism rate for all people] “I think they should set up vocational schools, where incarcerated people get real job training. And you move on from there to on-the-job training, earning paychecks to put money in the bank for when you are released. I think that would benefit everybody.”

Cramer knew Pezzeca 17 years ago in SCI Huntingdon. Pezzeca was sending letters to legislators, and Cramer thought it was a waste of time.

DC: “But all those years of writing to people — that’s how he made connections — that’s how he put the May 23 event together.”

Cramer agreed to speak on May 23. He noted that prison staff rarely shake the hands of incarcerated people.

DC: “Going out there and you got senators and representatives and people from the central office willing to shake your hand and get to know you. To me, it was a system shock. And then to have to get up and speak. It was a very overwhelming experience, but I was glad to be a part of it.”

In prison, training dogs, creating art

Dominick Serratore and dog Ranger (WW Photo: Joe Piette)

DS: “It was a middle-class life with a lot of child abuse. It was a very strict upbringing. My father was a state trooper. He was a disciplinarian. You can imagine my dad being in the position he was in, and with the homicide — it was his friends that picked me up, his friends that made the phone call to him. So it was a big embarrassment and hurtful for them. I never lived a criminal lifestyle. It was a shock to them. They just wanted to wash their hands and be done with me.”

DS: “It took some months, but my family including a brother, two sisters and nieces and nephews have supported me with lawyers, regular visits every chance they get.”

In 2001, the Pennsylvania Department of Correction began a program in which incarcerated people train dogs. Now 18 Pennsylvania prisons have incarcerated dog handlers who train puppies to become service dogs or to be adopted in local communities. Serratore’s job in prison is training dogs. Serratore brought one of the dogs, named Ranger, a German shorthaired pointer, to the interview. They both participated in the May 23 Seminar.

DS; “Lt. Gov. Davis asked about the dog program. I told him we’ve adopted out over 900 dogs. They’re very well trained when they leave, understanding basic commands like sit, stay, down, recall, walk on heels; some play frisbee; some play fetch. Some you point at them with your finger, they fall down and they play dead. It depends on the animal; how smart they are and how much energy they have.

“I have five things that I’m really big on — animals, nutrition, health, self-help programs and music/art. We’ve done a few murals in here. I did one 25 feet tall by 100 feet wide, with two full-sized eagles, a full-size elk and characters from Sesame Street. We painted bleachers on the wall in our gymnasium with people sitting in them, including Howard Cosell, Muhammad Ali, John Madden, Jack LaLanne, Einstein, and they’re all sitting in the stands. Everybody gets a kick out of it.”

WW: What about second chances?

DS: “I think only if we deserve it. I think they could look at the things we’ve accomplished. Look at the things we’re doing today — the things we want to do tomorrow. And you look at that over a long, extended period of time, you know, 20 years, 25 years. If you’re doing all the right things for the right reasons for that period of time, there should be a body of people that look at our conduct and give us that chance.”

In the mid-’90s, Pennsylvania made commutation almost impossible, requiring a unanimous vote from the Commutation Board to release anyone.

DS: “At the seminar, they did talk about getting the vote down to 4-to-1. I think that would be a monumental step. Lt. Gov. Austin Davis said he has the support of the governor for that.”

DS: [Referring to the seminar], “I think it was good to put faces to the bills or with the things that legislators are pushing for. Meeting with people, hearing them speak, hearing what we’re doing. I think that was important.”

Compassionate Release law = secret death penalty

Bryant Arroyo (WW Photo: Joe Piette)

BA: “I want to thank PA DOC Acting Secretary Dr. Laurel R. Harry and SCI Coal Township Superintendent Thomas S. McGinley for not only collaborating with us to come together on such an unprecedented and historical event, the first criminal justice seminar. To me it was remarkable. For once, in my entire 30 years, I’ve seen the men come together, and regardless of our particular differences, whether we like each other or not, everybody pulled up and played their part. And they definitely left an indelible mark across the board with the people that they met.

“Since SCI Coal Township’s construction in 1993, this is the first time that a lieutenant governor or any legislators, senators and state reps ever came here to attend such an event.”

Arroyo was instrumental in winning the compassionate release of Bradford “Bub” Gamble in 2021, who passed away just a few months after his release, because the state statutes didn’t allow him to take any medical treatment to treat the cancer that was killing him.

BA: “It’s shocking to me Pennsylvania legislators passed statutory laws like the Compassionate Release Statute 42 Ba, CS 9777 preventing terminally ill prisoners from receiving treatment in order to get compassionate relief. What they’ve created, in reality, is suicide relief. Blood is on their hands. This is a secret death penalty in the state of Pennsylvania.

“Former Gov. Tom Wolf and current Gov. Josh Shapiro both declared a moratorium against the death penalty, but there’s a secret death penalty. They need to expeditiously legislate a bill for those that are terminally ill and the elderly to be able to not only get treatment, but, once doctors declare a person to have a terminal illness, to be released within a few weeks and get them home or to hospice.

“The main opponent we have to contend with is Lisa Baker, who’s the chair of the Judiciary Committee. In 2009, she put in place this current statute which is not compassionate in any way, shape or form.

“There’s no mechanism in place for releasing prisoners who have served decades in prison and are medication dependent. Yet, when these lawmakers find the time to go to a prison and meet prisoners face to face, they’re amazed and astonished at our intelligence, remorse and our ability to express our heartfelt pain from the harm we caused. Perhaps if they visited prisons more often, they would comprehend the change in our humanity, and they wouldn’t be so quick to pass or keep in place legislation that brings about death by incarceration.”

At the seminar, Arroyo, who began his speech in Spanish, handed a Spanish translation of the Commutation Application to Board of Pardons Secretary Shelly Watson and Lt. Gov. Davis. He told them “the Board of Pardons and Commutations do not provide a Spanish language application for the Latinx prison population. This presents an outright constitutional violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment.

BA: “I also pointed out to Davis that once a terminally ill incarcerated person files a compassionate release application with the courts, there’s no mechanism to speed up the process for commutation. If a positive decision was rendered in a timely manner for commutation, it would allow the terminally ill to receive treatment for their insidious disease.”

It’s a significant step forward that incarcerated people in Pennsylvania are organizing themselves to fight for the simple recognition that they are human, that they can change over time, that keeping them incarcerated until they die decades later is nothing less than cruel and inhumane. Reforms to Pennsylvania’s criminal and prison statutes are long overdue. Ending life without parole and giving ill and elderly people an opportunity to live out their last months and years outside of prison with their families shouldn’t be seen as radical reforms.

Those in positions of power who continue to resist those reforms are confirming what Angela Davis said in a 1971 interview: “Prisons are concentration camps for the poor.”