COVID and prisons: No walls, no borders in the workers’ struggle

Texas

“It’s a nonviolent protest going on right now because the officers [in an unnamed Texas prison], in the middle of the coronavirus, have refused us electricity for several hours, no showers or anything.” The voice is that of an incarcerated human being on video taken inside a Texas prison. The grainy images show smoke wafting across the cellblock, where men shout in the dark.

Desperate to draw attention to their untenable situation, dozens on lockdown throughout the Texas prison system have started fires in their cellblocks and other living spaces, and made videos of the fires for family members, advocates, and media outside the walls. But even as COVID-19 rages — 26,000 infections; 168 deaths, an undercount — inside these walls, Texas prison administrators, similar to guards shown in the videos, “pay no attention.” In many of the videos, no fire alarms sound because they are broken, and have been since 2012. (tinyurl.com/yc4sxgm6v)

Saskatchewan, Canada

“Saskatoon Correctional houses over 500 inmates [142 of whom are infected with COVID-19], with 16 units, six of which are dorms that house 30 or more sentenced/remanded inmates, living in close proximity, sharing bathrooms per unit with no chance of social distancing,” said Cory Charles Cardinal, a member of the Cree Nation incarcerated in the Saskatoon prison. Cardinal was a participant in a late November hunger strike protesting conditions that have allowed COVID-19 to spread like wildfire among the people locked inside. Cardinal added that “Three living units are double bunked, also sharing one bathroom per unit, with unlikelihood of social distancing.” Cardinal said that he and another prisoner were transferred to the segregation unit because of their participation in the strike. (tinyurl.com/ycbda73w)

NOTE: While Indigenous people make up just 16 percent of the population of Saskatchewan, they are 65 percent of those in provincial prisons, and 75 percent of those in the jails. (tinyurl.com/ybak2du2)

For the Mississippi photo here is the credit: Rogelio V. Solis, January

Oklahoma

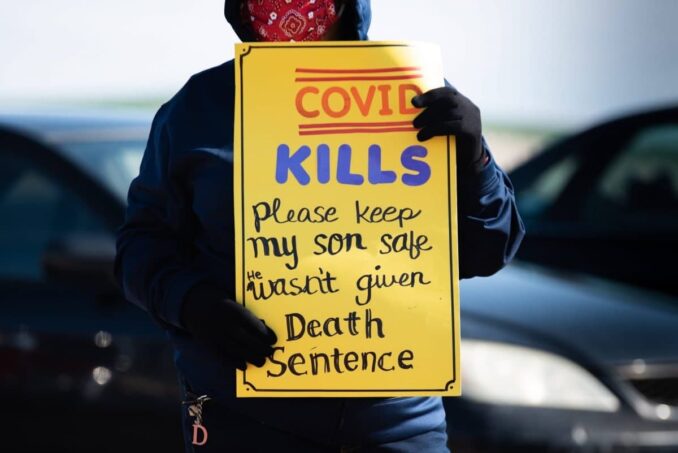

“Some guards would sit there and talk down on us, and tell us if we hadn’t gotten caught and weren’t in prison we wouldn’t have to deal with [the coronavirus],” said Stephanie Avery. Formerly incarcerated in Bassett prison, she was attending a recent demonstration against COVID-19 conditions within Oklahoma prisons, held in the cold and snow at the state Department of Corrections in Oklahoma City.

One in four of those locked behind the walls in Oklahoma have tested positive for COVID-19, and 36 have died. Avery added, “They said this is our fault and we deserve this.” One guard told her, “I don’t care if you get sick” after she and 112 of her sister inmates at Bassett prison became infected with COVID-19. She said the women suffered badly.

Now that she’s out, she has joined Ignite Justice, a 1,000-member Oklahoma support organization of people formerly incarcerated and families of those still inside. A co-founder of Ignite Justice, Emily Barnes, who has a son in Davis prison in Holdenville, Okla., said, when asked if her protests would hurt her son: “When [the prison authorities] see you’re not scared of them and you’re not going to back down, they’re not going to do anything.” (tinyurl.com/ybg9krpc)

California

“Though the leaders have suspended the hunger strike [against rampant coronavirus], our workers’ strike remains alive,” said a striker/spokesperson inside the California Substance Abuse Treatment Facility in Corcoran. The largest prison in the state, it is at 130 percent of capacity!

The hunger strike and the work strike — refusal to perform prison jobs — were called because of the widespread growth of COVID-19 inside the prison. There are currently 859 cases and three have died. Each week more than 100 prisoners are becoming infected in this prison alone. Statewide among incarcerated people, there are at least 6,000 active cases, and 90 have died. A participant in the hunger strike, David S. Cauthen, Jr., 32, said, “I have lost all hope in humanity because of how [the state prison system] has failed to protect individuals like myself.” (tinyurl.com/y7lzo3on)

Mississippi

“Parchman is a prison farm plantation,” said Jaribu Hill, a longtime Mississippi human-rights attorney. “Shut it down!” “Shut it down!” shouted back hundreds of protesters on Dec. 18 at the State Capitol in Jackson.

In December 2019, 10 incarcerated people had been murdered, on top of a dozen more over the previous two years.

Though cellphones are illegal in Mississippi prisons, the incarcerated still get them and send their families, supporters and media shocking videos of people going to the bathroom in garbage bags, killing rats in filthy cells, steel beds with no mattresses, and putrid food with live cockroaches crawling over it.

Even before COVID-19, Mississippi prisons were deathtraps for incarcerated people. Since the beginning of the pandemic, with an absolute worsening of living conditions inside, more than 90 have caught the virus and died. At present, the prisons administration reports 900 infections, certainly an undercount.

Brittany Bell, sister of Charoyd Bell, an incarcerated person at East Mississippi prison in Lauderdale County, told the crowd of protesters: “I feel like the issue here is that because these people are incarcerated, they are not deemed worthy to have the same amount of protections that we are out here, even though they are in even more closely confined spaces with even less capability to social distance on their own.” (tinyurl.com/yxyqo6c8)