Growing threats to workers’ homes

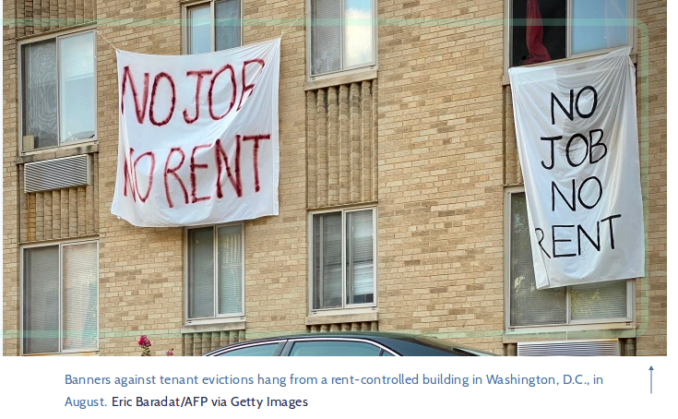

A rent-controlled apartment building, Washington, DC.

In March and April, over 22 million workers in the United States lost their jobs. So far, the stumbling economic recovery has brought 12 million back, but 10 million workers — 90% of them in the low-paid service sector — still do not have a job.

A majority of these workers are women. Service sector job losses and remote schooling have had a major impact on Black and Latinx women; at least 824,000 Latinx women have left the labor force since February. (NYT, Nov. 3)

It’s hard to get a true picture of what is happening in the job market and the overall economy because conditions and policies are changing so rapidly. It is not clear how many long-term (over 26 weeks) unemployed there are, because the labor force participation rate — the percentage of the working-age population working or actively seeking employment — is so low, even lower than it was in the 2008 Great Recession.

For the week ending Nov. 14, initial claims for state unemployment were slightly above 743,000, a jump from the previous week, and there were 320,000 claims filed with the federal unemployment programs. This doesn’t indicate a real economic recovery with more jobs being created.

How long an unemployed worker gets benefits, and what happens to them when benefits are exhausted, varies from state to state. The government’s priority is to keep workers from fraudulently getting state benefits, not to guarantee workers get what is their due. In some states, workers’ benefits have been held up when their claims are wrongfully flagged as fraudulent.

Mass evictions on the horizon

One thing is clear. This pandemic is hitting low-income renters very hard. The Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University reports more than half of renters who earn less than $25,000 a year lost wages between March and September. “While 15% of white renters at that income level are behind, 25% of Black and Hispanic renters are behind,” said Chris Herbert, the center’s managing director. This is another reflection of the systemic racism in U.S. society.

There will be major economic fallout from this crisis. The Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia has estimated U.S. renters will owe roughly $7.2 billion in unpaid rent by December. While evictions don’t clear up back rent, they do give landlords a glimmer of future revenue.

There is a strong possibility that a tsunami of evictions will begin in January 2021.

The CARES Act, the pandemic relief bill that Congress passed in March, prohibited evictions in buildings with a federally guaranteed mortgage — about half of the market for renters was covered.

There was a lot of confusion about these restrictions. Landlords and tenants had trouble finding information; complex paperwork was required to prove that inability to pay was COVID-related. Some landlords resorted to “private” evictions — changing locks, taking away the front door, stopping maintenance, hiring thugs — most of which are illegal because they lead to strife and violence.

The Centers for Disease Control stepped in and restricted evictions on the grounds that they would contribute to the current health emergency. Various states and even some cities passed similar restrictions.

Even in states like Arizona and Arkansas, where tenant protections are scarce, court-supervised evictions fell sharply, and “private” evictions were sometimes reversed. Still, Princeton’s Eviction Lab has counted over 100,000 eviction filings during the pandemic in the 25 cities it tracks.

However, these prohibitions against evictions are scheduled to sunset Dec. 31. There are predictions that as many as 4.1 million eviction cases will be filed in the first month of 2021. And the CDC’s order and the CARES Act just postponed the rent’s due date; the measures didn’t forgive rent debt.

While many renters are struggling to stay afloat and avoid the catastrophes that homelessness would bring, the big bourgeoisie in this country are doing swell. Business Insider (Oct. 30) estimates that U.S. billionaires increased their wealth by half a trillion dollars in 2020, while 40 million U.S. workers applied for unemployment insurance.