History will absolve me – the July 26, 1953, attack on Moncada Barracks, Cuba

Sometimes reality surpasses fiction. In a way, this is the case with the Cuban Revolution. Seventy years ago, a few dozen young rebels stormed a barracks. Even though the attack failed completely, it was the beginning of a revolutionary process with far-reaching consequences not only in Cuba, but also far beyond.

On July 26, 1953, the rebels stormed the Moncada barracks in Santiago de Cuba.

The assault

On July 26, 1953, a hundred young rebels led by Fidel Castro stormed a barracks in eastern Cuba. It was supposed to be the beginning of an armed uprising against the dictatorship. The aim was to obtain weapons and distribute them to the local population. The revolution would then be proclaimed over the radio.

In a second phase, the rebel army would retreat to the mountains and start a guerrilla war. The bold plan failed due to setbacks and above all due to lack of experience. Fidel was barely 26 years old. Most of the rebels were brutally slaughtered; only a few managed to escape. Fidel, his brother Raúl and several others were rounded up and put on trial.

Why an assault?

The rebellion did not come out of the blue. A year before, Fulgencio Batista had staged a coup. Cubans then lived under a military dictatorship, inequality between rich and poor was extreme, and the living and working conditions of the majority of the population were miserable.

Moreover, the country was under the control of the U.S. Officially, the country had gained independence in 1898, but all along the Cuban bourgeoisie had been too weak to establish a stable political system and to chart its own sovereign course, independent of the U.S. Batista’s increasing grip on society only exacerbated that situation.

Discomfort was very high. Many longed for a different, just society. Fidel Castro was one such person. He was a young lawyer and had been politically active since his student days. Originally, he thought of using parliament as a springboard for a revolution.

Together with the most radical members of the party he belonged to (the Ortodoxos), he would propose a revolutionary program from the parliamentary benches. That would then be the platform for mobilizing the masses to take armed action and to overthrow the government.

However, Batista’s coup shattered those plans, and it was clear to Fidel that there was no other option than direct armed uprising. Initially, young Castro expected that the revolution would be prepared from various quarters, and he intended to join them. But after seeing very little progress, he started his own movement.

He built a disciplined, clandestine movement from scratch, without financial resources and without support from any political party. He mainly recruited young people among the Ortodoxos and after a good year, he had 1,200 fighters at his disposal.

Political victory

The attack on July 26 failed, but Fidel managed to turn this military defeat into a political victory. The assault of the barracks was the start of a revolutionary process with far-reaching consequences in Cuba — and also in Latin America and Africa.

At his trial, Fidel Castro made an impressive plea that would later be published as “History Will Absolve Me.”

The trial was a real turning point: Fidel’s movement gained strong public awareness and recognition. During his time in prison, the revolutionary lawyer consolidated and educated his movement. His popularity gradually increased among the population. When presidential candidate Ramón Grau gave a speech in late 1954, Fidel’s name was chanted.

Soon after, a pro-amnesty campaign was launched. There were demonstrations in several cities, and the press also called for his release. The call for amnesty increased and on May 15, 1955, Fidel and his comrades were allowed to leave prison.

Once free, Fidel broadened his 26th of July Movement to include a number of key revolutionary leaders. The violence continued and things became too dangerous for him. That was why Fidel decided to go to Mexico to prepare the armed struggle from there.

In Mexico, Argentine doctor Che Guevara joined the rebel group. The rebels prepared for a protracted guerrilla uprising in Cuba’s mountains, supported from the towns, with the intention of disintegrating the army.

Armed insurrection

At the end of November 1956, about eighty of the rebels made the crossing [from Mexico to Cuba] on the Granma, a small yacht. The whole operation turned into a complete fiasco. Shortly after landing on Dec. 2, they were spotted, hunted, harassed and driven apart. In the end, barely sixteen inexperienced and poorly armed comrades-in-arms were left. Facing them was the best-equipped army in Latin America.

In other words, the situation was hopeless, but the rebels refused to give up. They received support from the local farmers and were able to consolidate. They managed to stay out of the grip of the army and after a few weeks, they won their first small victories. Herbert Matthews, a top New York Times journalist, was invited to the mountains in mid-February 1957. He was impressed by what he saw there and reported about it in his newspaper. That gave the rebel army’s prestige a huge boost.

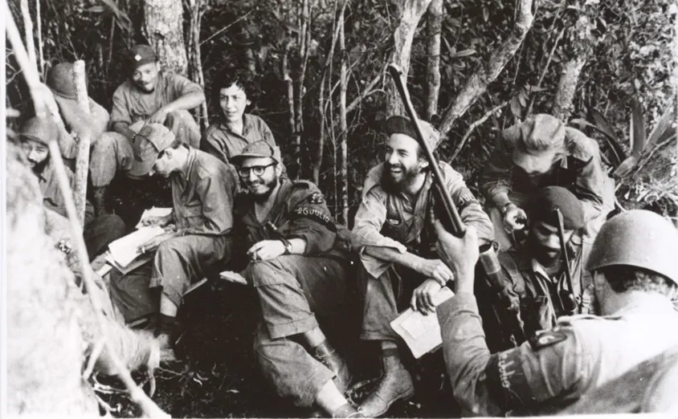

The July 26 movement in the Sierra Maestra. Photo: Cuban government

As the rebels achieved military successes, Fidel also gained more political support. In the summer of 1958, dictator Batista launched a summer offensive to deal a final blow to the guerrillas. The army’s numerical superiority was huge: 10,000 heavily armed soldiers against 300 rebels. After a month of fierce fighting, the rebels managed to beat back the army. That was a decisive turning point in the armed insurrection. With victory in sight, large sections of the national bourgeoisie also sought rapprochement with the 26th of July Movement.

In August, the guerrillas’ final offensive began. Entire parts of the country became “liberated territory.” After Che Guevara conquered the city of Santa Clara and destroyed an armored military train, Batista fled on Jan. 1, 1959. The revolution was a fact.

Washington’s obsession

A broad transitional government with a moderate program emerged, but even that was unacceptable for to Washington. The U.S. controlled important parts of the Cuban economy, and it did not want to lose them. Above all, it was impermissible for a country barely 90 miles from the U.S. to take a progressive direction. Moreover, that could encourage other countries to follow Cuba’s example.

That is why [from Washington’s viewpoint] this revolution had to be nipped in the bud. In July 1959, six months after the rebels took power, U.S. President Eisenhower approved a program to undermine the revolution. This ranged from supporting counterrevolutionary groups, air and sea strikes, the assassinations of Fidel, to jamming radio and TV channels and making clandestine radio broadcasts.

But more was needed. A memo in 1960 by Lester D. Mallory of the U.S. State Department reads: “The majority of Cubans support Castro. . . . The only foreseeable means of alienating internal support is through disenchantment and disaffection based on economic dissatisfaction and hardship. . . . every possible means should be undertaken promptly to weaken the economic life of Cuba.”

According to the memo, the aim was “to decrease monetary and real wages, to bring about hunger, desperation and the overthrow of the government.” Shortly afterwards, the Eisenhower administration imposed an embargo that would later result in an economic blockade, which also put pressure on third countries to end their economic relations with Cuba.

The first aim of economic sanctions was to overthrow the revolution, and if that failed, to hurt the country as much as possible so that socialism would not be an example for other countries. Chomsky called this Washington’s frantic “dedication to crush Cuba.” (Global Policy Journal, March 31, 2021)

The role of the Soviet Union

For its economic development and security, Cuba initially sought the support of Western countries which, under pressure from Washington, refused their support. Given the embargo, the military threat and the reluctance of Western countries, Cuba therefore very quickly relied on the Soviet Union for foreign trade and arms purchases.

The cooperation did not always run smoothly and after the 1962 missile crisis it even came to a real crisis between the two countries. Nevertheless, cooperation with the Soviet Union [over three decades] largely compensated for the losses caused by the economic blockade.

Economic disaster

Hence the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 was dramatic for the Cuban economy. Twice within barely 30 years, the island lost its privileged economic partner and had to look for new partners.

For any country, such a thing is disastrous. For Cuba, this loss was compounded by the U.S. tightening the economic blockade in the hope of draining the country economically. Without the blockade and without the fall of the Soviet Union, Cuba would have a standard of living comparable to that of Italy.

In socio-economic terms, the 1990s were extremely difficult anyway. But the country trudged through, and from the start of the millennium, it could count on the support of Venezuela. That gave the economy a boost. But, unfortunately and not coincidentally, Venezuela was in turn hit by economic sanctions from the U.S. from 2017 onwards.

This situation came on top of the further tightening of the blockade on Cuba since Trump’s election and the COVID-19 crisis, which hit Cuba hard due to the shutdown of tourism. As a result, the current socio-economic situation is particularly difficult, as it was in the 1990s.

Look after the people

It is therefore all the more remarkable that, despite these precarious economic conditions, Cuba has a very high level of social development. The island has a health care system that can compete with those in rich countries, while having a gross domestic product per capita that is at least five times lower. Child mortality is lower than in the U.S. and the educational system is the best in Latin America.

A World Bank report describes this as follows: “Cuba has become internationally recognized for its achievements in the areas of education and health, with social service delivery outcomes that surpass most countries in the developing world and in some areas match first-world standards. Since the Cuban revolution in 1959, and the subsequent establishment of a communist one-party government, the country has created a social service system that guarantees universal access to education and health care provided by the state.

“This model has enabled Cuba to achieve near universal literacy, the eradication of certain diseases, widespread access to potable water and basic sanitation, and among the lowest infant mortality rates and longest life expectancies in the region.”

According to the World Wide Fund For Nature (WWF), Cuba is the only country that has managed to combine an ecologically sustainable footprint per capita with an acceptably high quality of life as measured by the U.N. Human Development Index. That’s a comforting thought: if Cuba can do that without the latest and most economical technology, how much easier must it be for us [in Europe]?

The tenderness of the people

Cuba not only cares for its own inhabitants. “Solidarity is the tenderness of the people,” said Che Guevara. The Cubans give shape to this in an impressive way. From the beginning of the revolution, Cuba has supported sister countries in the Global South. Since the beginning of the revolution, Cuban medical personnel have treated nearly 2 billion people worldwide.

Today, Cuba single-handedly deploys more doctors worldwide than the U.N. World Health Organization. If the U.S. and Europe made the same effort as Cuba, the shortage of health workers in the Global South would be solved overnight.

Neither did Cuba hesitate to undertake dangerous military missions. For example, there were international missions in Vietnam, Syria, Algeria, Ghana, Congo (Brazzaville), Zaire, Equatorial Guinea, Zimbabwe, Ethiopia, Somalia, Eritrea, South Yemen, Tanzania, Angola, Namibia and Guinea-Bissau and support for various guerrilla movements in Latin America.

On the African continent, tiny Cuba was an important counterweight to the U.S. superpower from the 1970s to the 1990s. The Cuban army dealt a decisive blow to the apartheid regime of South Africa in Angola. Nelson Mandela recognized it [Cuba’s victory at Cuito Carnavale, Angola, in 1988] as “a turning point in the struggle to free the continent and our country from the scourge of apartheid!”

Fidel Castro and Mandela in 1991, a year after his release. Photo: Cuban government

Along with Venezuela, Cuba was the pacesetter for the integration of Latin American countries at the expense of Washington’s hold on the region.

Decision-making

Our [Belgium’s] economy and political systems are dominated by transnational and large capital groups. In Cuba, that power was broken and has been replaced by the CTC, the umbrella organization of the various union federations. There is no doubt that decision-making in Cuba is highly streamlined. But that is compensated by a form of direct democracy.

In addition to five-yearly parliamentary elections, there is a fairly unique consultation system. For all important decisions, the population is extensively consulted and a consensus is sought. No measures will be taken in Cuba without broad support.

This explains, among other things, why the Cuban government can count on enormous popular support despite often very difficult circumstances and the fact that it managed to hold out all these years against the largest and most aggressive superpower ever.

If we had this decision-making system [in Belgium], a wealth tax would have been implemented long ago and the retirement age would not have been raised to 67 [as it was in the U.S.]

Errors and challenges

A revolution is not made by angels. It is evident that mistakes have been made in the past 60 years. Just consider the humiliating treatment of religious believers and homosexuals at the beginning of the revolution, the failure to diversify the economy and to enhance productivity. The Cubans themselves are the last to claim that their journey has been without problems.

Many weaknesses and problems remain to be addressed. Perhaps the most important challenge is this: The high level of social and intellectual development creates high expectations among the population. But there is no economic basis for this, and that leads to frustration. This problem has become very acute in recent years.

This is closely related to another phenomenon. Due to the collapse of the currency after 1991, wages are no longer adequate. As a result, there is no longer a real link between labor, salary and purchasing power. This is very detrimental to labor motivation and productivity. It also causes corruption and discontent.

The only answer is accelerated economic growth, but promoting growth is easier said than done, because the foreign context is a strong determinant here. Will U.S. President Joe Biden ease the blockade for now? And who will be the next U.S. president? How is the situation in Venezuela and Latin America evolving? How are economic relations with China, Russia and Europe evolving? What will be the impact of the increasing number of droughts and devastating hurricanes?

The future will show whether Cuba will be able to solve these challenges. In these times, with the rise and spread of the alt-right, solidarity with a country that, for 60 years, has demonstrated “the tenderness of people” and where the focus is on people, not on profits, is more necessary than ever.

The process that the rebels led by Fidel Castro started 70 years ago with the attack on the Moncada barracks remains a beacon for the world. ¡Hasta la victoria siempre!

Katrien Demuynck and Marc Vandepitte wrote several books on Cuba.