Victor Toro can stay in U.S., but with no ID

At an April 30 immigration hearing in New York for Chilean activist Victor Toro, the U.S. government changed its stance and stopped trying to show that Toro was a “terrorist,” but at the same time refused to honor his appeal for political asylum.

The hearing itself showed that Toro has strong support, as nearly 40 people came out to be with him and show their solidarity during the hearing.

Toro, who has been living in the U.S. without documents since 1984, told Workers World at a May 1 demonstration the next day that it was surprising that “the U.S., after calling me a ‘terrorist’ for five years, dropped that completely. Now they say I could live anywhere within the United States. That is an 180-degree turn.”

At the same time, Toro points out that the authorities “refuse to give me papers establishing a legal condition for me here. I rejected their proposal and there will be a further hearing on the question on Oct. 23.”

Toro was a co-founder of Chile’s Movement of the Revolutionary Left (MIR), one of the parties that defended the government of Salvador Allende from the military coup of Sept. 11, 1973. He was arrested months after the coup and spent three years in prison, where he was also tortured.

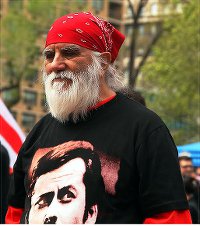

At the hearing in U.S. federal court this April 30, Toro wore a T-shirt with the face of Miguel Enríquez on it. Enríquez was secretary general of the MIR in the 1970s and was killed by Gen. Augusto Pinochet’s forces in September 1974. Many MIR leaders and activists were among the thousands murdered by the U.S.-backed Pinochet regime.

The Pinochet regime finally released and deported Toro in 1977, when after temporary stays in Sweden, Switzerland and France, he wound up in Cuba. His spouse, whom he met in the concentration camp in Chile, was there with him. Toro said that she had been tortured even worse than he was by Pinochet’s police.

Two years later, in order to more effectively carry out his political activity, he left Cuba for Mexico, Toro said at the hearing. Fearing that if he stayed in Mexico he would be hunted down by Gen. Augusto Pinochet’s secret police — part of the infamous Operation Condor — he entered the United States clandestinely in 1984.

While the political situation has changed in Chile since the days when Pinochet was ruling the country, Toro points out that his is a special situation. He was declared “dead” in Chile, a device the government used to prevent people from returning. Being officially “dead” means he doesn’t have even the normal protections that citizens would have.

He stayed with his spouse, Nieves Ayress, and their daughter for the following decades in the U.S., making their home in the Bronx, where they now have deep roots in the community. Both Toro and Ayress have been organizing for decades and head La Peña del Bronx, a multi-issue fightback organization. Ayress and their daughter, Rosa Victoria Toro, both have legal status in the U.S.

In 2007, Toro was racially profiled while riding an Amtrak train in upstate New York. He was detained by Department of Homeland Security Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents and issued a “Notice of Intent To Deport” him. He has been fighting this order since it was issued. The next step in that battle will take place at the 26 Federal Plaza courthouse on Oct. 23. n