Militarizing the Arctic

Think cutting shipping time from six weeks to less than three weeks is attractive to manufacturers? The Northern Sea Route through the Arctic can do just that, thanks in part to climate change. But sanctions have at least temporarily ruled out that option.

Think cutting shipping time from six weeks to less than three weeks is attractive to manufacturers? The Northern Sea Route through the Arctic can do just that, thanks in part to climate change. But sanctions have at least temporarily ruled out that option.

Until very recently the U.S. media coverage of the Arctic has focused on climate change, polar bears, melting ice roads, sea ice loss and oil leases. But what is going on in the higher latitudes is considerably more complex.

Relations between competing countries with regard to the Arctic are becoming as toxic and bitter as in the rest of the world. Russia, with so much at stake in the Arctic, has been building up its military capacity in the region for the last two decades. (The Worker/Denmark [Arbejderens], March 23)

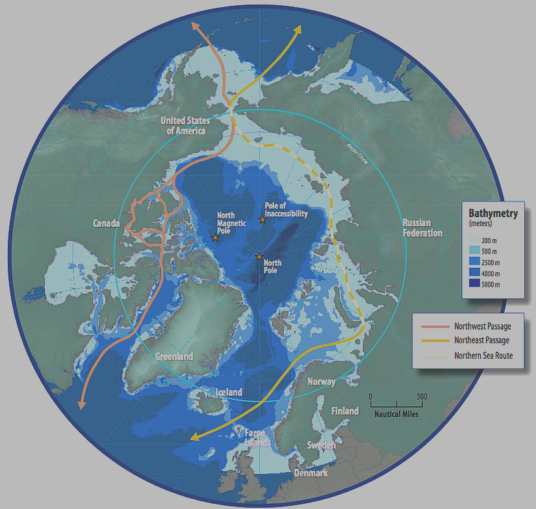

Eight countries have some of their territory within the Arctic, a harsh environment largely located above the Arctic Circle beginning at 66.6 degrees latitude. Over half the sea coast along the Arctic Ocean is part of Russia. The rest is unequally shared by Canada, Denmark (through its control of Greenland), Norway, Finland and the U.S. (the north coast of Alaska). A tiny sliver of Grimsey, an island off the north coast of Iceland, lies above the Arctic Circle as well.

The Arctic Council is an intergovernmental body headquartered in Tromsø, Norway, a small Norwegian city about 200 miles above the Arctic Circle. This council was first established in 1996 to provide a forum for Arctic countries, including Sweden, to work on common problems.

It also includes organizations of Arctic Indigenous people who first settled the region several thousand years ago: the Aleut International Association (AIA); the Arctic Athabaskan Council (AAC); the Gwich’in Council International (GCI); the Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC); the Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North (RAIPON); and the Saami Council.

Four million people, many Indigenous, live in the Arctic. The machinations of the United States and its allies like Canada are threatening their existence, their cultural integrity, their livelihoods. They deserve our solidarity and support.

The Council has worked on environmental and development issues, facing large and difficult problems relating to climate change, high latitude pollution, conflicting territorial claims, maritime transportation, infrastructure needs and resource exploitation. These discussions are now taking place in an increasingly tense political setting.

Military matters are not part of the Council’s responsibilities. Cooperation broke down after the Ukraine War, because seven of the countries refused to work with Russia, made more problematic because Russia was chairing the meetings. With the admission of Finland to NATO and the pending membership of Sweden, all countries in the Council are in NATO, except of course Russia.

In addition to the original eight countries who share the Arctic and six Indigenous organizations, the Council has added 13 non-Arctic permanent observers, including China, France, Germany, Britain, India, South Korea and Japan. These countries are eager to be included in Arctic discussions and decisions, because a warming climate means there will be new resources coming from both the land and the seabed. And especially, there will be new transportation opportunities along the northern sea routes that will cut weeks off the time it takes for goods to move between Asia and Europe.

The Northwest Passage through Canadian waters is actively being developed but is much trickier given the existence of many islands. While much of the annual ice there is now absent for longer periods of time, the water is deeper and the ice retreats to passages between islands, remaining hazardous to year-round shipping.

Military and political agendas affect the Arctic

There is now “a significant Russian military buildup in the High North,” according to NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg. NATO forces monitor the Baltic and North Seas, while projecting a presence in the Arctic. This comes after Russia withdrew “as much as three-quarters of its land forces from the High North region near the Arctic” to send them to fight in Ukraine. (CNN, Dec. 22, 2022)

The U.S./NATO forces have been matching the Russian efforts with a buildup of their own, doubling NATO’s presence with ships, submarines and patrol aircraft. War games were held in March 2022, within days of the Russian entry into Ukraine. Known as Cold Response, these games are held every two years enabling the NATO forces to rehearse coordinating and commanding personnel and supplies from 27 different countries, with no common language, under Arctic conditions.

The U.S. announced last week that it will open a consular office in Tromsø later this year to monitor Russian moves in the region.

The U.S. has expanded its military presence and training to enhance its Arctic preparedness. The USS Gerald R. Ford, the largest aircraft carrier in the world, is operating in Norway’s Arctic waters under NATO command. There are currently 150 jets from 14 NATO nations training in the region, more above the Arctic Circle than at any time since the breakup of the Soviet Union.

Other U.S. destroyers, aircraft carriers and submarines are in the area as well. Some are part of Arctic Challenge 2023, a biannual large-force, live-fly field training exercise to advance Arctic security initiatives and enhance interoperability of the NATO forces. (Air National Guard website, June 2)

Massive Russian oil and gas deposits

Russia has a big stake in the Arctic, particularly developing and bringing to market their massive oil and gas deposits. About 90% of Russia’s current gas production and 60% of its oil production are there. (Arbejderens, March 23) It is aggressively developing the necessary infrastructure, building ports, refineries, shipping capacity and icebreakers needed for shipping along the Northern Sea Route, or the Northeast Passage, to speed up shipping between Europe and Asia.

Sanctions imposed by the U.S. and European Union have cut into current demand by other countries for shipping along this route, but these countries do not expect the advantages of this route will be out of reach forever. Russia is going to have difficulties building and maintaining its icebreakers, which are powered by nuclear reactors. The sanctions, which the United States imposed, limit Russia’s access to the technology these ships use. Spare parts and software updates are particularly affected.

FSUE Atomflot is a Russian civilian facility located just north of Murmansk. For three decades it has received grants and major investments from Norway, Britain, the U.S. and the European Union, which let it develop and improve its ability to process and transship spent nuclear fuel from dump sites on the Kola Peninsula. On May 20, the U.S. added FSUE Atomflot to its sanctions list.

The Russian Minister for the Development of the Far East and the Arctic, Alexei Chekunkov, said, “While a number of unfriendly states are trying to revise previously announced plans for transit along the Northern Sea Route, we are seeing a growing interest in using the route from China, India and countries in Southeast Asia.” (Barents Observer, June 2)

Read an article at workers.org/2021/09/59128/ from two years ago on the same development.