Conflict grows as President Moïse buried in Haiti

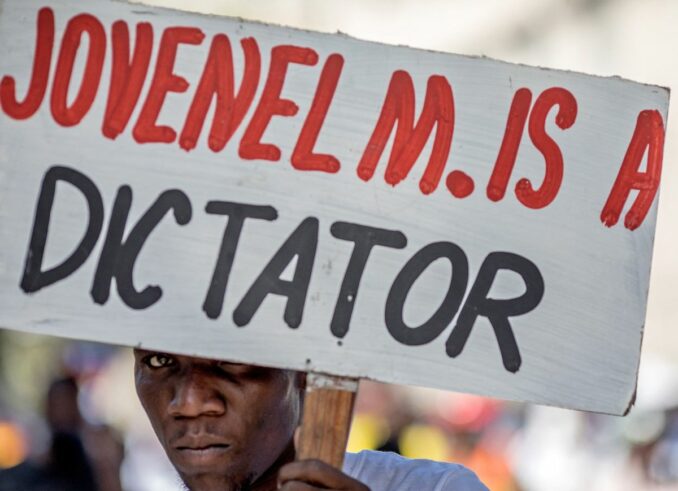

Demonstrators march in Port-au-Prince on February 14, 2021, to protest against the government of President Jovenel Moise.

Wearing a Kevlar bulletproof vest, Martine Moïse praised her late spouse, assassinated President Jovenel Moïse, at his July 23 funeral in Cap-Haïtien, for “defending the poorest against the cupidity of the elites” and striving to reform “a rotten and unjust political system.” Using Haitian Creole and French, she attacked the “oligarchs who have won a battle but not the war.” (haitilibre.com, July 24)

The hundreds of thousands of Haitians throughout the country that came out time and time again over the years that Moïse ran the country to protest him and his policies obviously disagree with her. Protests outside the Moïse family compound in Cap-Haïtien wafted tear gas, smoke from burning tires and the sounds of gunfire into the ceremony — which the Moïse family made a point of paying for.

After gunshots were heard, U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Linda Thomas-Greenfield, heading the U.S. funeral delegation, hastily left, driving directly to the airport at high speed over the rough roads in northern Haiti, according to the video on the NBC website. The White House announced the delegation’s safe return.

A large demonstration called for justice for Moïse in Trou-du-nord, his hometown, about 20 miles past Cap-Haïtien on the way to the Dominican Republic. There was also a major pro-Moïse demonstration of Haitian expats in Paris a few days earlier.

The U.N. and various religious NGOs report that the number of internally displaced individuals is growing in Haiti and that the increased political instability is preventing people from earning enough to feed themselves and their families. The percentage of food-insecure individuals — people who don’t regularly get enough to eat to sustain themselves — is 48%, one of the highest rates in the world.

The BBC and the Washington Post report that bandit activity along coast roads — especially around Port-au-Prince — is so great that drivers take ferries rather than roads.

New York Times exposes U.S. control

The 10 Haitian senators, still in office because their terms are staggered, met a few days after the assassination and appointed president of the Senate, Joseph Lambert, as provisional president. One of the constitutions that might be in force — there are some disputes about which one is currently operational — suggest that they followed the correct procedure. But after Lambert made a few phone calls, he suspended his campaign. He had no apparent support in Washington.

According to the June 23 New York Times, politicians, business people, political parties and the Haitian government itself have been spending tens of thousands of dollars on lobbyists and political consultants in Washington.

According to the Times, a group chat among some Haitian politicians and officials and their U.S. advisors “showed them strategizing about countering American critics and potential rivals for the presidency and looking for ways to cast blame for the killing.” The Haitian government paid an outfit called Mercury Public Affairs at least $285,000 for six months work and continues to pay $67,000 a month to a consortium of public relations firms.

Beyond all this maneuvering, there are Haitian businesses and individual politicians that want to whip up interest for their projects, even if they have to shell out for this interest from their own pockets.

When the NY Times tries to explain Haitian history, because this history has a direct bearing on what the U.S. can do now, it often leaves out some inconvenient truths. A July 25 article entitled “We Owe Haiti a Debt We Can’t Repay” correctly points out that “[i]nstead of welcoming and supporting the fledgling republic, the United States refused to recognize Haiti until 1862, after the Southern states seceded from the Union.”

The article then concludes with the U.S. occupying Haiti in 1915 “after the assassination of President Vilbrun Guillaume Sam.”

It doesn’t mention that a Marine raiding party, shortly before the 1915 occupation began, slipped into Port-au-Prince and seized Haiti’s gold reserves — worth at that time around $500,000 — and turned them over to First National City Bank in New York — now Citibank.

This is indeed a debt that the U.S. could indeed repay — with interest.