Socialism and trans liberation

The following are selected comments from panelists at an April 1 webinar: “Transgender Day of Visibility: a Socialist Perspective,” sponsored by Workers World Party, viewable at Workers World YouTube: tinyurl.com/35944sht. WWP comrades Ezra Echo, Devin Cole and Romeo Channer were joined by Dr. Susan Stryker, author of “Transgender History: The Roots of Today’s Revolution”; Jupiter Peraza, an undocumented trans woman, activist, DACA recipient and program associate for the Transgender District of San Francisco; and Indigo Lett, the secretary and social media coordinator of the Gulf Coast transgender activist organization STRIVE.

Trans history, trans borders

Ezra: Can you elaborate on the history of how the trans movement has been built in the U.S. and some of the struggles the movement has allied with?

Susan: The trans movement actually dates back in the U.S. to the 1890s. A group was formed in New York City at a place called Columbia Hall, which was a kind of combination bar, beer garden, performance venue, hookup site, sex worker hangout and hotel. Then there was this group called the Cercle Hermaphroditos in NYC that was mostly trans femme people, who called themselves androgynes, who said that they came together to unite for common defense against the bitter persecutions of the world.

Trans activism really starts to take off as a minority identity activist movement in the 1950s and 1960s. A journal called the Society for Equality in Dress was publishing back in the 1950s. You start to see people advocating for the ability to change names on legal documents in the early 1960s. When the social movements of the 1960s get started, you see trans people organizing in street politics and being engaged in radical direct action against policing and incarceration.

I made a film “Screaming Queens: The Riot at Compton’s Cafeteria,” about trans women in the Tenderloin [neighborhood] in San Francisco, who would hang out at the all-night cafeteria, kind of the chill-out zone for the whole neighborhood. The cops would regularly raid the place, and one night in August 1966 — three years before the more famous Stonewall Uprising — the cops came in, and the queens fought back. As the best contemporaneous description of the event says, general havoc was raised that night in the Tenderloin.

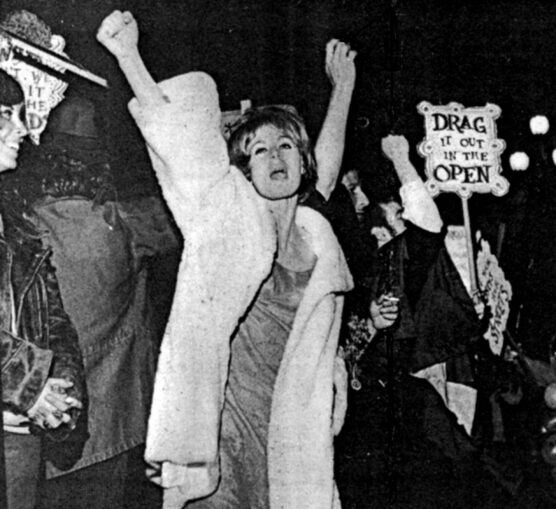

The ‘riot’ at Compton’s Cafeteria, San Francisco, 1966.

I feel particularly in the 21st century, post 9/11, a lot of what trans people have faced in terms of violence is state-based violence that has to do with borders — border crossing and identity documentation and access to social services. Trans people — we often get lumped under the LGBT umbrella, but in some ways, I think trans issues have less to do with sexual orientation issues than with questions about citizenship status, who gets to be counted as a member of the body politic.

And so trans activism is very much aligned with pro-migrant, pro-asylum, pro-open borders kind of activism.

Jupiter: About how the history of the trans movement has been built in the U.S. — the trans movement has sort of made leaps as it’s attached itself to movements and faces in history. For example, the Industrial Revolution brought people to urban centers, in this geographical location where they weren’t known by anyone else. Because when you live in a small town, in a small village, everybody knows you; there’s this pressure of having to be very conservative and limited in the way that you express yourself. In the Industrial Revolution people were flocking to cities and experimenting with their expression.

Another example: After World War II ended, we saw the rise in international attention to Christine Jorgensen [a former U.S. GI who achieved sex affirmation surgery in Denmark in 1951]. She’s both seen as fun, and her participation in the war brings a new light and a new attention to the trans movement. And if you fast-forward some decades to the AIDS epidemic, you also see trans people being impacted and trans issues being brought forth in a new light.

But historically, cisgender heteronormative issues are highlighted more than trans people. That is something that I believe trans people have always struggled with. Everything that happens, we really need to bring attention how this impacts transgender people. For example, within the Black Lives Matter movement, with the murder of Black trans women, we are now experiencing the cry that “Black Trans Lives Matter!” This is a perfect example of how we can highlight trans struggles in whatever is currently happening right now — with police brutality, for example.

I will say I think we’re doing an incredible job in understanding trans issues and strengths and in bringing attention to trans struggles to make this a better society for trans people.

Trans struggle for socialism

Ezra: Why is it critical to fight for socialism in order to secure trans liberation?

Romeo: Perhaps a very obvious point is that health care is a human right — and access to health care is especially necessary and urgent for trans folks. It’s one of the biggest battles being fought for by trans folks across the world. If you live in a socialist country, that provides health care for all its people.

Devin: You can’t have socialism without trans liberation, and you can’t have trans liberation without socialism. Capitalism and imperialism are designed and created to divide people, including by gender — to build oppression on gender.

Even though there are people who believe that transgender is not that big of a deal in the fight for socialism, it’s critical! We had Comrade Leslie Feinberg, a member of Workers World Party for well over 40 years, who intricately and meticulously laid the connection out that gender oppression arose as part of class oppression, in hir Marxist historical analysis, “Transgender Warriors.” The fight for socialism is the fight for trans liberation, and vice versa.

Susan: To actually achieve a just and livable and sustainable society that treats everybody fairly — where everybody has enough, nobody’s got too much — we have to think about the U.S. in particular, the settler-colonial dimension, the fact the U.S. is built on stolen labor and stolen land. For me, socialism is just the belief, the conviction, that you can, in fact, have a just social order. And if a system of governance doesn’t address that, it’s still settler colonialism.

Indigo: For me, socialism is understanding how bad capitalism is. For working-class people, we need to understand the economic point, obviously, and the point about racism, but we also have to understand the international point — understand the U.S. role as a country and how that affects other people in other countries. Historically there are third-gender communities everywhere, and they are affected by colonialism and capitalism!

Then especially last year with the pandemic, that really showed we need so much — health care, education and so many other things. That leads us obviously toward socialism. With the administration we have now, they’re basically going to try to get us back to where the U.S. was before the pandemic — which was still a very terrible place! So I think for us, it’s just a constant, constant unlearning of our own toxic behaviors, to continue learning more about ourselves and pushing toward socialism in a way that we can all feel welcomed and comfortable and alive.

Romeo: I just want to add that I personally won’t feel liberated if the hormones that I take are being manufactured on stolen Palestinian land, which is where a lot of hormone replacement therapy comes from. That’s just one of many, many examples of how all these struggles across the globe are materially linked. Not only in the way we need to look at structures and deal with structures, but there is the actual material physical connection that globalization and capitalism have tied together. Our gender is still being controlled and policed to a great extent by these systems of capitalism and imperialism.