Supreme Court ‘justice’ is theft from workers

A recent U.S. Supreme Court decision that allows companies to replace collective lawsuits with individual arbitration is going to make wage and time theft from workers more likely. The May 21 decision involved three cases, Epic Systems Corp. v. Lewis, Ernst & Young LLP v. Morris and National Labor Relations Board v. Murphy Oil USA.

A recent U.S. Supreme Court decision that allows companies to replace collective lawsuits with individual arbitration is going to make wage and time theft from workers more likely. The May 21 decision involved three cases, Epic Systems Corp. v. Lewis, Ernst & Young LLP v. Morris and National Labor Relations Board v. Murphy Oil USA.

Under the combined decision, nonunionized workers will find it much harder to recover the wages they have earned but have not been paid.

Wage and time thefts are big problems costing workers billions of dollars.

Wage theft occurs when time you have worked “on the clock” is not paid. Often this happens when a worker quits or gets fired in the middle of a pay period, and management just “forgets” to send you your last paycheck. Or the bosses have a policy for not paying for time spent cleaning up your workstation, or not paying for your travel time when you start working at one store and then are asked to go to another which is short-staffed. And so on and so on.

This kind of chiseling affects all workers but is particularly hard on low-wage workers. A 2014 study by the Economic Policy Institute established that “the average [wage] loss per worker over the course of a year was $2,634, out of total earnings of $17,616. The total annual wage theft from front-line workers in low-wage industries in the three cities approached $3 billion.” The survey covered workers in New York, Chicago and Los Angeles.

Extrapolating from these results supports the estimate that wage theft costs low-wage workers in the U.S. $50 billion a year.

Can you imagine the outcry in the bourgeois press if low-wage workers each regularly stole $2,500 from their employers?

There is another way of looking at wage theft. You can compare it to crimes generally lumped under the category of “theft” by the U.S. so-called “justice” system. In 2012, according to statistics maintained by the FBI, there were 292,074 robberies of all kinds, including bank, residential, convenience store, gas station and street robberies. The total value of the property taken was $340,850,358 — an amount vastly less than the yearly wage theft from workers!

Stealing time

There’s another way workers don’t get what they’re due, called time theft. Here’s an example based on this writer’s own work experience.

In a print shop producing long-run jobs, once the presses started rolling workers were expected to keep them running, skipping lunch or dinner or breakfast, depending what shift you were on.

But the computer software used by management still assigned every worker a half-an-hour meal break, even if they worked through it.

So the 100 workers in this print shop involuntarily “contributed” 300 unpaid hours to their boss every week. (They generally worked 6 days a week.) When they complained to the wage-and-hours office in New Jersey, they were told that, for such a small claim (around $100,000 a year), they were better off getting their own lawyer. This reporter quit before a lawyer was found.

But after the recent Supreme Court ruling, workers like the ones in the print shop won’t be able to band together to get a lawyer. Legally, they would have to have 100 individual arbitrations of their claims. Practically, they would probably never ask for arbitration because the legal fees would be too much for them to bear.

Unions helpful but no panacea

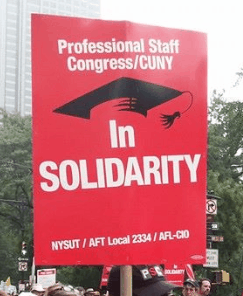

At the City University of New York, one of the largest universities in the country with nearly 280,000 students, a large proportion of its technical staff is in the same union, the Professional Staff Congress. The PSC also represents the faculty, both full-time and adjunct.

For decades, even though the contract between the PSC and CUNY called for a work week of 35 hours, the technical staff, especially at registration time, worked tens of hours of noncompensated overtime.

Then in 2002-03, the union filed and won a grievance about this practice.

CUNY management didn’t give in but came up with a compensation scheme so complicated that it is not adhered to. The scheme doesn’t protect staff from being obliged to work through lunch or put in extra time at the end of the day. But it does keep staff from being called in over the weekend without compensation and it is a positive step in protecting the staff.

Even though union representation may not fully solve worker grievances, union struggle, especially with worker militancy, can and does win concessions from management that improve workers’ lives.

Now unions, and especially those for public employees, are under a sustained and powerful attack, both by the Supreme Court and by the Trump administration.

The Supreme Court has a case, the so-called Janus case, that has the potential of being a major financial blow to public sector unions in 20 states. The Trump administration published a series of three executive orders the Friday before the Memorial Day weekend designed to severely limit the rights of federal workers.

“It’s basically an attempt to make federal employees at-will employees, so you can make them political employees, so you can hire anyone who had a bumper sticker for you in the last election,” said J. David Cox, president of the American Federation of Government Employees, the largest union representing federal employees.

These attacks are a call to all workers to follow the militant example of the education workers in West Virginia, Kentucky, Oklahoma, Arizona, Georgia, Michigan and Puerto Rico. These public employees marched, rallied, walked out and struck, most of them in “right-to-work” (for less) states. They acted for themselves, their students and their communities. They have shown the way to unite to push back against the capitalists’ theft of our wages, time and lives.