No justice in 1946 racist lynching

The Atlanta Journal Constitution announced in an exclusive report Dec. 28 that the FBI had “quietly closed its investigation into the murders” of two Black couples by a racist mob in 1946 at Moore’s Ford Bridge in rural Walton County, Ga. The Georgia Bureau of Investigation is expected to do likewise by the end of January, with no one held accountable.

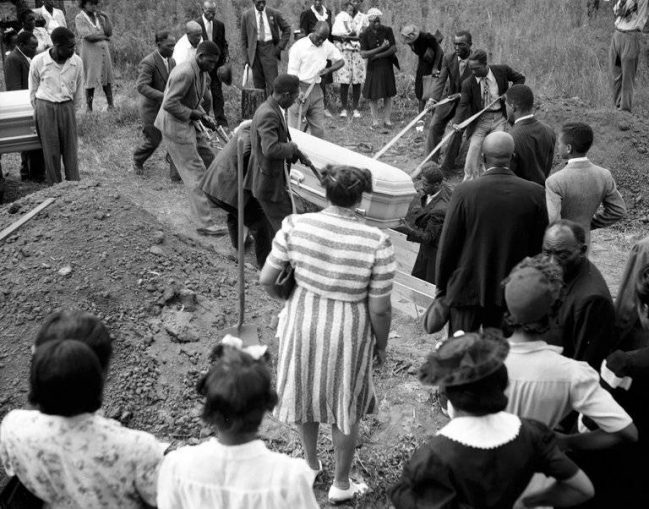

Often described as the “last mass lynching” in the U.S., the vicious, preplanned killing of Roger Malcolm, Dorothy Malcolm, George Dorsey and Mae Murray Dorsey reveals the conditions of white supremacy and violence that dominated throughout the former Confederate states.

The details of the case are well-known. Roger Malcolm had been involved in a physical fight with a white farmer, Barnette Hester, on July 14 and had stabbed him. Hester was taken to a hospital for treatment and Malcolm was held for 11 days in the county jail in Monroe, Ga.

White landowner Loy Harrison bonded Malcolm out for $600 on July 25. The Malcolms and Dorseys were sharecroppers on Harrison’s land. Accompanied to the jail by Dorothy Malcolm and the Dorseys, Harrison then began the drive toward his farm in the late afternoon.

Harrison said that when he reached the Moore’s Ford Bridge, about an hour later, his car was stopped by a band of dozens of armed men who forced the two couples out of the vehicle, beating them and riddling their bodies with 60 bullets at close range. Although the assailants’ faces were not covered, Harrison claimed he didn’t recognize anyone.

Dorsey was a World War II veteran who had served in the Pacific. Reportedly, Dorothy Malcolm was seven months pregnant. The brutality of the murders made national news, and the Truman administration ordered the FBI to send investigators to Walton County. There was no local police investigation.

Although thousands of FBI interviews over five months took place, and early attention was put on several members of the Ku Klux Klan, hostility and fear led a grand jury to indict no one. The suspects were provided alibis and no physical evidence was found.

Eyewitness says cops were there

The level of racist intimidation can be exemplified by the public beating of Lamar Howard, a Black man who testified before the grand jury that he had overheard two of the participants planning the ambush. Howard was later accosted at his job by two white men who, when arrested, admitted striking him repeatedly. Yet they were acquitted by a jury in short order.

Years would pass and the killers of Roger and Dorothy Malcolm and George and Mae Murray Dorsey continued to live and thrive in Walton County.

In 1968, just before he was assassinated, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. sent a young Southern Christian Leadership Conference staffer, Tyrone Brooks, to Monroe in advance of his planned visit to the town after his return from Memphis. As a teenager, King had written a letter to the Atlanta newspaper in 1946 denouncing the murders.

Brooks, who went on to become an elected state representative in the Georgia House, pursued every lead in an attempt to bring justice to the families of the Malcolms and Dorseys.

After decades of little new evidence, in 1991, Clinton Adams, a 55-year-old white man, told FBI agents that he and a boyhood friend had witnessed the murders while hiding behind some trees. He claimed to have seen a police vehicle on site and named names. Adams said he had been warned to keep quiet and for years as an adult he moved frequently, fearful of Klan retaliation.

Adams, haunted by what he saw as a 10-year-old boy, continues to hold to his recollection of what he saw that day. Nevertheless, with many of the likely participants dead by that time, no official charges resulted.

In 1997, a biracial group formed the Moore’s Ford Memorial Committee, which successfully secured a first-of-its-kind historical marker on Highway 78. Located near the turn-off to the lynching site, it notes the racist act that took place there on July 25, 1946.

In 2001, then Gov. Roy Barnes officially ordered the Georgia Bureau of Investigation to re-open the case, followed in 2006 by the FBI. The lynching at Moore’s Ford Bridge joined the list of many other cold cases of unprosecuted racist murders that took place during Jim Crow segregation.

In 2004, Tyrone Brooks approached the memorial committee with a dramatic proposal: to re-enact the murders and preceding events at the actual locations on the anniversary date.

Year after year, in late July, local residents and family members as well as people from around the world gather in Monroe to witness a vile crime that mirrors past and present systemic injustices committed with impunity.

More than seven decades have passed since four young Black people’s lives were ended by racist terrorists who were protected by a code of violent white supremacy.

The official investigation and legal prosecution by the capitalist state have ended, but the trauma and pain remain. They continue to spur on the struggle for real justice and liberation.

Mathiowetz has attended the re-enactment at Moore’s Ford Bridge multiple times and met the relatives of the Malcolms and Dorseys, who demand justice. See the book, “Fire in the Canebrake: The Last Mass Lynching in America” by Laura Wexler, 2003.