GE’s ‘moral fabric’ and its forgotten socialist wizard

Is General Electric one of the corporations “destroying the moral fabric” of the United States? That’s what Bernie Sanders told the New York Daily News editorial board on April 4.

GE’s CEO, Jeffrey Immelt, got so angry that two days later he attacked the presidential candidate in the Washington Post.

Judge for yourself whether GE is a corporate criminal.

Immelt bragged about jobs at GE facilities in Sanders’ home state of Vermont. He didn’t mention that Jack Welch — his predecessor as GE’s CEO — fired 112,000 workers.

Since 1978, the company has gotten rid of 22,000 jobs in GE’s hometown of Schenectady, N.Y., alone. That’s according to Thomas F. O’Boyle, author of “At Any Cost: Jack Welch, General Electric, and the Pursuit of Profit.”

GE workers called Welch “Neutron Jack” because he destroyed people’s jobs while leaving the factories intact, just as the neutron bomb was supposed to kill people with radiation while leaving cities’ infrastructure intact. Welch argued that, “ideally you’d have every plant you own on a barge,” so it could move to where the lowest wages were.

In Massachusetts alone, according to O’Boyle, GE fired 7,000 workers in Lynn and 8,000 in Pittsfield. Erie, Pa., saw 6,000 GE jobs evaporate while Fort Wayne, Ind., lost 4,000.

Nobody works at the 77-acre GE factory in Bridgeport, Conn., anymore. This factory employed 12,000 workers during World War II. The factory still employed 3,000 in the late 1970s, but the last 70 workers were let go in 2007. (Connecticut Post, March 23, 2010)

No wonder census statistics reveal that nearly a quarter of Bridgeport’s population lives in dire poverty.

Polluter and nuclear menace

Immelt also didn’t mention that GE’s two aviation plants in Vermont released 60,000 pounds of toxins in 2011, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

GE fought for decades against any EPA-imposed cleanup after dumping more than 1.3 million pounds of cancer-causing chemicals into the Hudson River. (cleanup.org) The company also poisoned Connecticut’s Housatonic River and, from another plant, the Coosa River Basin in Georgia.

Japan’s nuclear disaster at Fukushima, which started with a 2011 earthquake, involves five GE Mark 1 reactors. Three GE engineers — Gregory C. Minor, Richard B. Hubbard and Dale G. Bridenbaugh — quit in 1976 to protest the reactor’s unsafe design. (ABC News, March 15, 2011)

There are 23 Mark 1 reactors in the United States.

Tax havens and pension rip-offs

Immelt claimed that GE pays “billions in taxes.” But in 2010, GE paid zilch in taxes after making $14.2 billion in profits. It actually got $3.2 billion back in refunds from Uncle Sam that year. (New York Times, March 24, 2011)

Last year, GE held $119 billion in offshore profits in 18 overseas tax havens. (International Business Times, Oct. 6, 2015)

GE is moving its headquarters from Fairfield, Conn., to Boston after getting promises of $25 million in property tax breaks over 20 years. Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker also wants to provide GE with $120 million in new roads, parking and utility improvements. (boston.com, April 8)

At the same time, Boston is threatening new public school cutbacks.

Immelt didn’t reveal in his Post article that GE will be slashing medical benefits for retirees, allowing the company to save $3.3 billion. (thestreet.com, Aug. 4)

In 2014, Immelt got $37.2 million in total compensation, more than $100,000 per day. Nearly half of this package is because of a big increase in his pension. (Reuters, March 10, 2015)

The socialist founder of GE labs

GE also tried to destroy UE, the Electrical Workers union, with red-baiting attacks and helped propel Ronald Reagan’s political career.

With this record, is it any surprise that GE has “never been a big hit with socialists,” as Immelt wrote in the Washington Post?

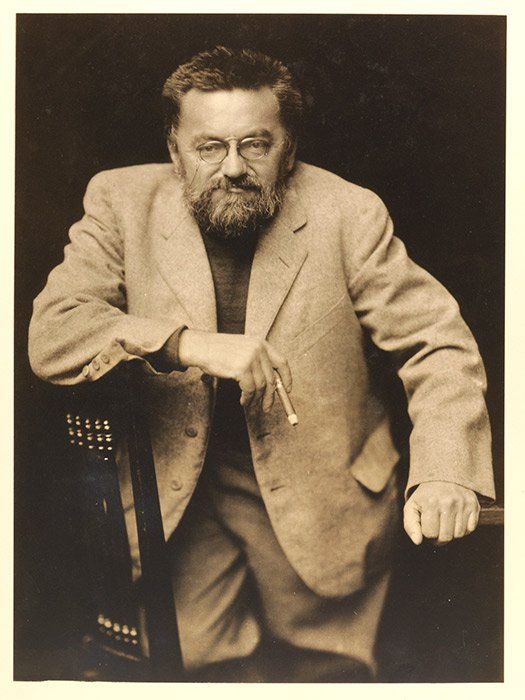

Yet the founder of the GE Research Labs was the socialist Charles Steinmetz. The first industrial research facility in the U.S. started in Steinmetz’s Schenectady, N.Y., garage in 1900.

Charles Steinmetz was born in the German empire in 1865. As a university student he was forced to flee the country because of Bismarck’s anti-socialist laws.

Attempting to enter the U.S. in 1889, he was initially turned away by immigration officials. Steinmetz had kyphosis, a curvature of the spine, and only $10 in his pocket. Donald Trump would have deported him.

A gifted mathematician, Steinmetz worked out “Steinmetz’s Law,” which figured out the heat loss, “hysteresis,” in electric motors. This paved the way for developing alternating current power. Steinmetz, along with others, created the first commercial three-phase power system.

By 1900, Steinmetz was the most famous electrical engineer in the world and was known as “the Wizard of Schenectady.” Helping to protect Steinmetz’s 200 patents at GE was the African-American engineer and inventor Lewis Latimer.

Steinmetz helped elect George R. Lunn as Schenectady’s socialist mayor in both 1911 and 1915. Another GE town, Bridgeport Conn., also had a socialist mayor — Jasper McLevy — from 1933 to 1957.

Charles Steinmetz became president of the city’s school board, where he provided free meals for hungry students. Judging from his other positions, Steinmetz would have been thrilled by the Black Panther Party’s Breakfast for Children programs.

A supporter of unions, Steinmetz changed cigar brands when cigar makers went on strike. In 1922, Steinmetz got 291,000 votes when he ran for state engineer and surveyor on the Socialist Party/Farmer-Labor ticket in the New York state election.

A. Philip Randolph got 129,000 votes running for secretary of state on the same ticket. Randolph later led the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and initiated the 1963 March on Washington.

Steinmetz welcomed the socialist revolution in Russia. He wrote the introduction to “The Industrial Revival in Soviet Russia,” by A .A. Heller.

On Feb. 16, 1922, Steinmetz wrote Soviet leader V.I. Lenin of his “admiration of the wonderful work of social and industrial regeneration which Russia is accomplishing under such terrible difficulties.

“I wish you the fullest success and have every confidence that you will succeed. … If in technical, and more particularly in electrical engineering matters, I can assist Russia in any manner with advice, suggestions, or consultation, I shall always be very pleased to do so, as far as I am able.”

Lenin wrote two warm letters to Steinmetz in response. But before Steinmetz could help, he died on Oct. 26, 1923.