The need for internationalist solidarity

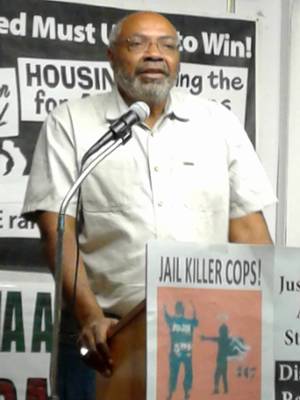

Following are edited remarks delivered to the U.S. chapter conference of the International League of People’s Struggle held in Chicago on Oct. 22. Azikiwe is an internationally known anti-imperialist leader from Detroit.

There is a fundamental weakness in the people’s movement in the United States, and that is the necessity for anti-imperialist internationalism.

The struggles against racism, national oppression and class exploitation cannot be separated from the need to end Washington and Wall Street’s interference in the internal affairs of most states throughout the world.

Winning recognition in these monumental struggles is heavily dependent upon the degree to which we can create widespread awareness of the plight of communities of color and the working class in general. There are efforts underway to achieve these objectives although much more work has to be done.

International consciousness in regard to the character of the U.S. state is growing immensely. This is in part due to the mass demonstrations and urban rebellions which have sprung up by and large spontaneously in response to the vigilante death of Trayvon Martin in 2012 and the not-guilty verdict handed down in the trial of George Zimmerman.

When Zimmerman’s acquittal was announced it did a great deal to turn public opinion domestically and internationally against institutions which devalue African-American life and democratic rights. It was during this period that the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter began to trend. Since then there have been efforts to build BLM chapters across the U.S., spreading internationally into Britain and Latin America.

Later, on Aug. 9, 2014, in Ferguson, Mo., 18-year-old Michael Brown was gunned down by a white police officer. Immediately, demonstrations erupted in Ferguson. These manifestations spread nationally, bringing attention to the false notion that the U.S. had become a so-called post-racial society in the period following the election of President Barack Obama in 2008.

No ‘post-racial’ U.S.

Obama was forced to address the problems of the “special oppression” of African Americans after the unrest in Ferguson. The situation of African Americans gained international attention prompting editorials in leading periodicals both in the U.S. and internationally questioning this false assertion of post-racialism.

The administration leaned in favor of maintaining the status quo of national oppression. Obama, of course, gave his view of what “African Americans feel” and then denounced violence, saying it will not accomplish anything. This is a blatant falsehood because the U.S. state was born in violence and maintains its existence through brute force and coercion inside the country and abroad.

What these developments further exposed was the failure of the Obama administration to address the special oppression of African Americans while instead advancing a policy of public avoidance in the face of worsening social conditions.

It was the African-American masses and other oppressed groups who suffered the brunt of the economic crisis beginning in 2007. Detroit was one of the hardest hit urban areas. When Obama came into office in 2009 there was considerable false hope that these economic difficulties would attract the attention of the White House and the then-majority Democratic House and Senate (2008-10).

Subsequent rebellions and waves of mass demonstrations in the streets, campuses and now athletic fields have stripped the administration of any pretense of political legitimacy. Colin Kaepernick and others in professional, college and high school sports settings illustrate that no matter how they are classified as “privileged,” the specter of racist violence and threats from the armed agents of the state remains with them at all times. Racism is on the increase in the U.S., and the refusal of the ruling class and the capitalist state to advance any reforms in this regard speaks volumes about the current phase of imperialism and its public posture.

Global implications of capitalist crisis

The degree to which the capitalist class can claim any semblance of an economic “recovery” is related to the expansion of low-wage labor and the mega-profits of transnational corporations. This is reinforced by the systematic defunding of public education, municipal services and environmental safeguards.

There are examples too numerous to outline here. We could speak about the undemocratic system of emergency management and forced bankruptcy in Detroit and other Michigan cities that have majority African-American populations. There is also the water crisis in Flint and the near collapse of public schools in Detroit, Highland Park, Inkster and other Michigan cities.

A nationally coordinated movement led by trade unions demanding a minimum wage of $15 an hour is growing across the country. People of all generations are working more for less money.

The prison-industrial complex, now encompassing approximately 2.2 million people, with millions more under judicial and law-enforcement supervision, represents another form of super-exploitation and social containment that is connected to racial profiling and the unjust court system.

These are some of the principal issues we must take up in the U.S. Our internationalism must be informed by the specific conditions of the workers and oppressed and the movements that have sprung up in the last four years.

Drawing links between home and abroad

Perhaps the most profound crisis of displacement today is the migration of people from North Africa into southern Europe. This movement of dislocated persons has been documented by the United Nations Refugee Agency as the largest since the conclusion of World War II. There are 60 million to 75 million people who have been internally and externally displaced in the modern world.

These forced removals stem directly from the foreign policy imperatives of war and economic exploitation engineered by Washington and Wall Street. The interventions in Afghanistan, Iraq, Haiti, Libya, Syria, Yemen and Somalia are fueling underdevelopment and balkanization.

Many of these wars remain largely hidden from people in the U.S. Much of the social impact of these wars of regime change and genocide are being manifested inside these geopolitical regions and in southern, central and eastern Europe.

The crisis of imperialist war has its economic components. The overproduction of oil and other commodities is driving down prices and causing higher rates of joblessness, poverty, food deficits, class conflicts and civil war. Countries such as Somalia, South Africa, Zimbabwe and Nigeria, rich in natural resources, land and strategic waterways, are facing varying levels of recession, depression and further enslavement to international finance capital.

Finally, it is our task to point to the direct relationship between U.S. domestic and foreign policy. A policy of national oppression inside the U.S. is reflected in the military and economic destruction of countries from the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, and extending across Africa, the Middle East, Asia and the Pacific, Latin America and the Caribbean.

The problems we are facing in North America cannot be effectively tackled or solved independent of the people of the international community. The world’s peoples must unite in a program of anti-imperialism aimed at ending all forms of oppression and exploitation.