Louise Michel and the Paris Commune of 1871

Paris, March 18, 1871. The National Guard, the workers’ militia that was defending Paris from the besieging Prussian Army, rang the alarm at dawn. But it wasn’t the Prussians who were attacking. It was France’s regular army, following orders from the capitalist-monarchist Parliament sitting in the Parisian suburb of Versailles.

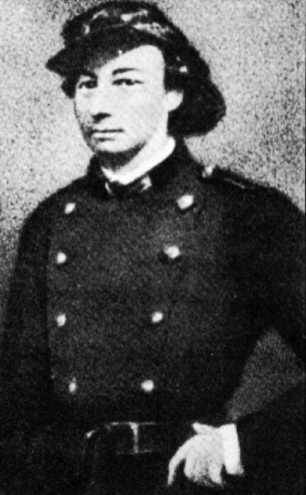

Louise Michel was among those in the hills of Paris’s Montmartre district who were defending the cannons under the people’s control. One can imagine the gray-haired Michel, a 50-year-old schoolteacher who was to become the outspoken leader of the Women’s Union for the Defense of Paris and Aid to the Wounded — l’Union des Femmes — hurrying from block to block, mobilizing her forces.

August Thiers headed the 1870-1871 government that had replaced Louis Napoleon’s Empire. Thiers had been prime minister of France back in June 1848, when he ordered the army to crush a workers’ uprising in Paris that had terrified the French capitalists. His priority in March 1871: disarm the National Guard and leave the workers’ organizations at the mercy of the Prussians.

Before dawn, Thiers sent 40,000 troops to collect the 300 cannon in Paris. The whole operation aimed at provoking a battle with workers that would lead to the mass arrests of their leaders.

In her memoirs, Michel wrote:

“The soldiers of the reactionaries captured our artillery by surprise, but they were unable to haul them away as they had intended, because they had neglected to bring horses with them.

“Learning that the Versailles soldiers were trying to seize the cannon, men and women of Montmartre swarmed up the Butte [hill] in a surprise maneuver. Those people who were climbing believed they would die, but they were prepared to pay the price.”

At 8 a.m., the people, and especially the women, begin to fraternize with the troops sent in by the Thiers government. At first, there was mutual fear. Then recognition. Soon there was to be solidarity.

Michel continued: “The Butte of Montmartre was bathed in the first light of day, through which things were glimpsed as if they were hidden behind a thin veil of water. Gradually, the crowd increased. The other districts of Paris, hearing of the events taking place on the Butte of Montmartre, came to our assistance.

“The women of Paris covered the cannon with their bodies. When their officers ordered the soldiers to fire, the men refused.”

Gen. Boulle, who commanded these regular troops, repeated his order. The troops again refused and the crowd moved closer. The general, now shaking with anger tinged with fear, gave his order a third time. Again the troops refused. And in another giant step, they pointed their weapons at the general, taking him prisoner.

Franco-Prussian War

What set the stage for these events was the war between France and Prussia. France’s Emperor Louis Napoleon, who had ruled since 1852, declared war on Prussia in the summer of 1870. Otto von Bismarck’s Prussian soldiers quickly trashed the French army, and 200,000 French troops were taken prisoner.

By the beginning of 1871, a siege of Paris by the victorious Prussian army and the ensuing collapse of the French economy had driven the already poor population into near starvation. With ruling-class arrogance, the monarchists and capitalists ruling France from the town of Versailles, outside Paris, actually demanded that the already destitute tenants and small shopkeepers pay up their rents.

The only serious defenders of Paris against the Prussian invasion during this period were the troops of the National Guard. This was an army of volunteers, especially strong in the districts with the poorest workers, many of them unemployed, and the impoverished shopkeepers.

At around 10 a.m. on March 18, the Thiers government learned that the troops of Gen. Faron had also fraternized with the people and abandoned their weapons to them. At 1 p.m., Gen. Claude Lecomte was grabbed by the celebrating crowd and by his own soldiers. Gen. Jacques-Léon Clement-Thomas, who commanded the troops that had buried in blood the workers’ uprising of June 1848, was also captured.

At about 3 p.m., the revolutionary National Guard was marching en masse past the ministry where the heads of the government were meeting. Frightened by the power of the armed masses, Thiers decided to leave Paris for nearby Versailles and ordered all the troops to retreat from Paris and all the government officials to leave also.

The victorious people, furious over the presence of the hated generals, stormed the post where the generals were being held. They executed LeComte and Clement-Thomas. Most of the bullets came from the rifles of the mutinous regular army soldiers. Before midnight, the uprising had seized the National Guard headquarters, the central police headquarters and Paris City Hall. It held most of the city.

Military mutiny gave birth to workers’ power

While at dawn on March 18 the central committee of the National Guard had merely set out to defend themselves from a military coup, by midnight they had, de facto, seized power. This was Day 1 of the 72 days the Paris Commune existed, the democratic rule of the poor, led by the working class.

This uprising of Parisian workers was the essential prologue to the European revolutions of the twentieth century. It was the first revolution in a European capitalist society where the wage workers — the working class or modern proletariat, those who live by selling their labor power — succeeded in setting up their own government and their own state. And this Paris Commune burst into existence through a soldiers’ mutiny in the army of the French Empire.

The Commune could exercise its power only within the city of Paris, which was the capital, largest city and largest working-class center in the centralized capitalist state of France. Commune rule arose in some of the other major cities, like Lyon and Marseille, but could not sustain itself outside Paris. And conversely, without support from the provinces, the Paris Commune was unable to control the destiny of France. Nevertheless, the historical lessons from this first workers’ revolution allowed revolutionary leaders to prepare to carry out revolution in the next century.

The theoretical leader of the International Workers Organization, Karl Marx — who with Friedrich Engels had written the “Communist Manifesto” in 1847 — saw in the Paris Commune the first historical experience of how the working class could overthrow the capitalist ruling class and begin to run society in the interest of all the oppressed classes.

The living experience of the Commune showed that it was impossible for the working class and oppressed sectors of the population to simply win over Parliament and start building a new social system. The old government, bureaucracy and armed forces were tied by innumerable strings to the old ruling class, and only by destroying this old state and building a new one, bound to the working class, could society be changed.

By the end of the day on March 18, 1871, most of the 50,000 rank-and-file troops of France’s regular army who had been in Paris had either changed their allegiance to the National Guard, deserted or been withdrawn from the city, while most of the French soldiers outside Paris were prisoners of the Prussians.

This meant that within Paris, the National Guard was both the political body directing the Commune and the armed force keeping order in Paris. The National Guard constituted the new state, which defended the unemployed, the workers, and the small producers and shopkeepers, all of whom saw the Commune as their government.

Marx, Lenin analyzed lessons of the Commune

Marx wrote of this in his pamphlet, “The Civil War in France,” published in 1871. Marx’s pamphlet became the basis for key chapters of the pamphlet “State and Revolution,” which the revolutionary communist leader V.I. Lenin wrote in the summer of 1917, on the eve of the Russian Revolution, an event which was to shape 20th-century history.

Lenin’s pamphlet provides as clear as possible an explanation of why it was necessary to smash the old state, which enforced capitalist rule, and replace it with a new state based on the rule of the working class. Only then could one change society.

For anyone seriously interested in a revolution that frees the downtrodden and oppressed, these two works are indispensable.

The Commune lasted only 77 days, but they were great days, during which laws were passed protecting the workers, poor and women — always defended by Louise Michel’s organization — and establishing a popular democracy.

The French ruling class and its government in Versailles responded with what — from the point of view of any French patriot — would have to be considered a “treasonous” deal with the Prussian generals. It ceded to the Prussians the province of Alsace-Lorraine; the Prussians, in return, released the French prisoners of war, whom Thiers used to drown the Commune in blood.

These troops had been held as prisoners far from Paris, far from the revolutionary Parisian workers. They came mostly from rural areas and remained brainwashed by the lies of the rulers in Versailles. In May, these troops obeyed their officers. They slaughtered the Communards who dared to defend Paris, including many of the women fighters of L’Union des Femmes, who were the most resolute defenders of the Commune.

Some 30,000 Communards were massacred and 43,000 more imprisoned or exiled to the French-held, South Pacific territory of New Caledonia (called Kanaky by the Indigenous people).

Louise Michel, who fought alongside the women and men defending the Commune, escaped the first wave of arrests. She turned herself in only after finding out the authorities were holding her elderly mother hostage.

In court, Michel refused to submit to the reactionaries or promise to hold her tongue in the future, demanding instead that they shoot her. This the rulers feared to do. Michel was among those sent to New Caledonia.

Epilogue: Uprising in Kanaky

In subsequent years, the Kanak Indigenous people of that island staged an uprising. Unfortunately, French imperialism was able to use many of the imprisoned Communards to fight against the Native uprising. Not Louise Michel, however. She distinguished herself as a revolutionary leader by standing in solidarity with the Indigenous uprising against French rule.

Here is an excerpt from what Michel wrote about the Kanak revolt of 1878:

“The Kanaks were seeking the same liberty we had sought in the Commune. Let me say only that my red scarf, the red scarf of the Commune that I had hidden from every search, was divided in two pieces one night. Two Kanaks, before going to join the insurgents against the whites, had come to say goodbye to me. They slipped into the ocean. The sea was bad, and they may never have arrived across the bay, or perhaps they were killed in the fighting. I never saw either of them again, and I don’t know which of the two deaths took them, but they were brave with the bravery that black and white both have.”

A large square in Paris is named after Louise Michel, and this revolutionary woman anarchist certainly earned this honor.

Source of the quotes: Maclellan, Nic. “Louise Michel,” Ocean Press, 2004. This article is adapted from a chapter in John Catalinotto’s forthcoming book, “Turn the Guns Around: Mutinies, Soldier Revolts and Revolutions.”