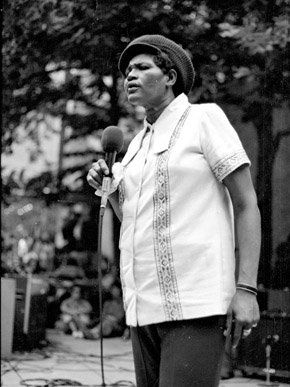

‘BIG MAMA’ THORNTON and reparations

You have probably heard of Elvis Presley and perhaps even heard him sing, “I ain’t nothin’ but a hound dog.” This was ”the signature song” that propelled him to fame and estimated lifetime earnings of $4.3 billion.

It is less likely you have heard of Willie Mae “Big Mama” Thornton. She first recorded “Hound Dog” in 1952 and received $500 in payment, her only earnings from the song.

The discrepancy between their fates has been described as “perhaps the most notorious example of the inequity that often existed when a black original was covered by a white artist,” says the Encyclopedia of Alabama. But the difference between Thornton and Presley is more than “inequity.”

This is injustice — pointing to the need for reparations to African-American people for the theft of Black music. An article titled “For Old Rhythm-and-Blues, Respect and Reparations,” published in the New York Times on March 1, 1997, describes the theft so shameful and pervasive that the Rhythm & Blues Foundation has been forced out of music corporations like Atlantic Records and Time-Warner.

The foundation money — far less than “reparations” — assists older African- American R&B artists who received few or no royalties from corporations and are now unable to pay medical bills and rent.

This meager money came years too late for Willie Mae Thornton. Her song, “Ball ‘n’ Chain,” made famous by Janis Joplin, was named by the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as one of the “500 Songs that Shaped Rock and Roll.” But in 1984, the year Thornton was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame, she died in poverty in Los Angeles.

Thornton was born in 1926 in tiny Ariton, Ala., on land seized from the Creek Nation for the slaveocracy’s large and small cotton plantations. Thornton was a descendant of Native peoples and enslaved Africans who labored under brutal conditions for no wages at all — and then were returned to virtual slavery as sharecroppers by racist, post-Civil War Jim Crow laws.

Thornton began to sing at an early age in the church where her father was the preacher. When her mother died, Thornton quit school and worked as a cleaner at a local tavern or “juke joint.” At the age of 14, she left home for good to sing on the road. She had a big voice, a big personality and was dubbed “Big Mama” by an Apollo Theatre emcee in New York after appearing there.

Many songs Thornton wrote, like “Willie Mae’s Blues,” have a strong woman’s perspective. (glbtqarchive.com) Some accounts say during her early years in the South, Thornton gave birth to a son who was taken away from her by the state.

Despite her gendered nickname, Thornton was thoroughly gender-transgressive. Once her career was more established, she usually performed wearing “men’s clothes” — workshirts, slacks and straw fedoras. Rumors flew that she was a lesbian, but her best friend said without judgment he’d “never got a handle” on her sexuality, having seen her with neither men nor women. (George Lipsitz, “Midnight at the Barrel House: The Johnny Otis Story,” University of Minnesota Press, 2013)

Nowadays Thornton might be considered trans* — but there is no way to know how she defined herself or what pronoun she might choose now. (Trans* is currently used with an asterisk to indicate the spectrum of all the different sexes and genders of people who do not conform to the either/or of male/female or masculine/feminine.) The pronoun “she” is used here as that was the pronoun Thornton used publicly during her life.

‘My singing comes from

my experience’

Only 26 when she recorded “Hound Dog,” Thornton said this of her music: “My singing comes from my experience. I never went to school for music or nothin’. I taught myself to sing and to blow harmonica and even to play drums by watchin’ other people!” (tinyurl.com/jjop3rw)

The music Thornton made came out of the collective work and experience of African-American people. In “Father of the Blues: An Autobiography,” W.C. Handy described the music he and other Black workers made with their tools at a Florence, Ala., foundry in the 1890s. They pulled and beat shovels against different metal parts while waiting for the furnace to process ore. (Da Capo Press, 1969)

Handy wrote: “With a dozen men participating, the effect was sometimes remarkable. … It was better to us than the music of a martial drum corps, and our rhythms were far more complicated. … The [African-American worker-musicians] accompany themselves on anything from which they can extract a musical sound or rhythmical effect. … In this way, and from these materials, they set the mood for what we now call blues.“

Big business has stolen — and continues to steal — huge profits from music made by Thornton and other Black performers. Those huge profits are just one example of the wages that have been stolen from African-American people in the U.S. over the centuries.

Every worker knows that unpaid labor is theft — and thus demands reparations.

The issue of reparations has been raised in the current U.S. presidential campaign. “Socialist” candidate Bernie Sanders said he thought reparations would be “divisive.” He recommended actions that apply to the general population, such as rebuilding cities, decent-paying jobs and free tuition for higher education.

But there was nothing more “divisive” to working-class unity than legal enslavement by the ruling class and later peonage of people of African descent — while using minimal economic bribes to get white workers to turn their backs. This divisive system of racism continues to the present day; this is especially apparent in the disproportionate number of African-American people incarcerated in the for-profit prison system.

Working-class solidarity in the U.S. requires that white workers show unity with African Americans in demanding reparations. That would be a step forward in exposing the crimes of capitalism. A demand for reparations reaches deep into U.S. history and shows that the foundation of the current economic system — the banks, railroads, agribusiness and cultural products — has been built on the sweat, blood, knowledge and songs of oppressed peoples.

Hear Thornton sing at tinyurl.com/hkk9ud8.