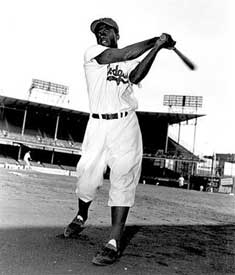

Cracking a racist wall

Jackie Robinson's historic impact

Published Apr 19, 2007 12:14 AM

On April 15, 1947, Jackie Robinson broke the so-called color barrier

by becoming the first African American to play in Major League Baseball. On

April 15, 2007, the 60th anniversary of this significant event, over 200 MLB

players and some managers of all nationalities wore Robinson’s retired

number 42 on their uniforms to honor him. The following are excerpts from an

April 10, 1997, article written by Mike Gimbel on the occasion of the 50th

anniversary of Robinson joining the then Brooklyn Dodgers. Go to www.workers.org/ww/robinson.html

to read the article in its entirety.

Robinson’s entry into Major League Baseball had a momentous impact on the

anti-racist struggle in the U.S. It even had an important effect on U.S.

imperialism’s political status on the world stage.

Jackie Robinson, perhaps the most exciting baseball player of his time, was

more than a “mere” athlete who happened to be in the right place at

the right time.

Robinson grew up in Pasadena, Calif., a town so racist that it took until 1997

to officially acknowledge his accomplishments.

Jackie Robinson went into the segregated U.S. Army, where he became an officer.

But he was court-martialed for failing to sit in the back of the bus at a Texas

army base. The case became a national political incident and the army was

forced to dismiss the charges against him.

Just as Robinson was no accidental figure, neither were those who chose him to

break the color barrier. Nor was it accidental that Major League baseball was

the arena for this historical event.

In order to understand the event in its proper context, one has to understand

the period in which it happened.

The USSR had defeated Nazi Germany in World War II, and in doing so had

liberated much of Eastern Europe from capitalist slavery. A huge liberation

movement, led primarily by communist parties, was sweeping Asia. The Western

powers, led by the U.S., were trying to break the workers’ movements in

France, Italy and Greece, where armed resistance to fascism had been led by the

communists.

The imperialist powers would have loved to present this as a struggle between

communism and “democracy,” but they had a big problem: They were

seen as racist oppressors on the world stage.

The Europeans still claimed most of the world as their colonies, and the U.S.

was propping them up.

The U.S. had its own colonial holdings in Puerto Rico and the Pacific. In

addition, the South was ruled by the Ku Klux Klan, an organization no better

than Germany’s Nazi Party. The South was solidly held by the Democratic

Party, and no Democrat could get elected president without the support of

racist “Dixiecrats.”

In 1947, the civil rights movement had not yet begun. The U.S. military was

still segregated and it would be seven more years before the “Brown vs.

Board of Education” Supreme Court decision declared “separate but

equal” schools to be unconstitutional.

But many Black soldiers were returning home after having risked their lives

abroad. They came back to racism, in the North as well as the South.

Yet there was a completely different political current. The U.S. left and

progressive movement was still very powerful. Communist Party membership hit

its zenith in 1947. Mass May Day marches were held all over the country replete

with red flags. The labor movement was involved in militant strikes and the

left had a huge influence in it.

The U.S. ruling class could not credibly portray itself as “leader of the

free world” while being perceived as the open oppressor of a large

portion of its own population. Something had to be done.

Truman and the Dixiecrats

President Harry S. Truman, however, dared not act without support from the

Dixiecrats. The U.S. ruling class seemed trapped by this quandary. The

politicians couldn’t find an answer to this problem, which was so vital

to U.S. imperialism. Another way had to be found.

Baseball became the arena where this struggle took center stage. Major League

baseball is a sport unlike any other.

For much of [the past] century baseball could almost be considered a national

religion. It is no accident that “tradition” is so highly prized by

the “Lords of Baseball.” Nor that the singing of the national

anthem has become such a prominent part of starting a game. Baseball is, after

all, the “national pastime.” U.S. presidents traditionally throw

out the first ball.

Had Jackie Robinson integrated professional football or basketball, he’d

be a forgotten figure today. But breaking the color barrier in baseball would

present a new image of the U.S. to the world.

However, the more far-seeing leaders of U.S. imperialism found that most of

their class was so racist they had no inclination to support integration at any

level.

Major League owners wouldn’t budge

The owners of the 16 Major League franchises were no different. These owners

were, if anything, more right-wing than most of their fellow businessmen. They

treated their teams as private plantations where they amused themselves with

their “toys.” They got some notoriety by getting their names in the

newspapers and/or used the teams to advertise their “real”

businesses.

There was no way these reactionary owners, as a group, would voluntarily allow

a Black player into the Major Leagues.

A few team owners might have been willing to integrate the Major Leagues, but

the overwhelming majority were not for it.

The Brooklyn Dodgers were the original “America’s Team.” The

“Beloved Bums” were second only to the New York Yankees as the

richest sports franchise in the world.

The team performed in New York City—the very capital of high finance and

home to the United Nations. The Dodger’s general manager was none other

than Branch Rickey, the most renowned front-office baseball figure of the

century.

He was considered the most far-sighted baseball leader. For the ruling class,

he offered the added bonus of being very religious and anti-communist, as well

as parsimonious when it came to paying the players.

The Dodgers were in the National League, considered a traditionally weaker

league. It was only natural that a far-sighted, practical general manager would

see the acquisition of Black players as a means of redressing this weakness and

making the team more profitable.

Rickey, together with Baseball Commissioner A.B. “Happy” Chandler,

planned the coup that got Jackie Robinson into the Major Leagues.

Rickey and Chandler used this power to get Robinson into the Major Leagues,

over the objections of almost all the other owners. For this

“treachery,” Chandler was bounced out as commissioner at the end of

his term.

Articles copyright 1995-2012 Workers World.

Verbatim copying and distribution of this entire article is permitted in any medium without royalty provided this notice is preserved.

Workers World, 55 W. 17 St., NY, NY 10011

Email:

[email protected]

Subscribe

[email protected]

Support independent news

DONATE